Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Choosing the ideal panel bender

A panel bender is an efficient, effective way to process thin, complex parts, but one size does not fit all jobs

- By Rob Colman

- November 29, 2016

- Article

- Fabricating

A panel bender is an effective metal forming machine for jobs involving materials with up to 1/8 inch thick. In one process, it is possible to rapidly complete a complex part that requires very accurate radius forming, hemming, or offset bends. The same operations performed on a press brake could be painstakingly slow.

“The use of time on a press brake actually moving up and down to produce a bend might be 15 per cent of an operator’s time,” said Bill Bossard, president, Salvagnini America. “The balance of time is spent handling parts, finding parts, doing first-article checks, etc. And what we constantly hear from customers is that they wish there were a way to minimize or eliminate setup time on a press brake. Everybody is trying to drive down setup time. But once you start adding automated features to a press brake to make that possible, the price rises high enough that a panel bender becomes a viable alternative.”

Any shop that produces a lot of box-shaped items – HVAC and cabinet jobs – in the right gauge may consider a panel bender a viable option. The question then becomes whether to choose a fully automated, semi-automated, or manually operated machine. The choice will come down to the type of work the shop is pursuing and price considerations.

Manually Positioned Options

To describe any panel bender as manually operated is somewhat of a misnomer. In the case of TRUMPF’s TruBend Center Series 5000 machine and Prima Power’s FastBend machine, the operator loads a part is onto the panel bender and all of the bends on one side of the part are performed at once.

On the TRUMPF machine, a part as long as 10 feet can be bent with an 8-in. nesting height. It accepts sheet as thick as 1/8 in.

This is TRUMPF’s first foray into the panel bending market. This machine was first unveiled in North America at FABTECH® Chicago in 2015. Tom Bailey, product manager for the TruBend series at TRUMPF, said that the company is trying to differentiate itself in this market by launching a bender that it feels is flexible in unique ways, such that it sets itself apart from fully automated models.

One of the ways the manufacturer differentiates its panel bender is the manipulator used to move the part once the operator has positioned it for bending. The manipulator is a 2-axis design, which moves the part both in and out for bends, but also vertically.

An auxiliary set of blank holders that can be moved into position automatically form narrow channels on a TruBend. Photo courtesy of TRUMPF.

“Most panel benders you see on the market use a single-axis manipulator that just moves a part in and out of the machine to complete bends,” said Bailey. “Being able to move the part vertically opens up some possibilities. For example, a traditional limitation of panel benders has been that you cannot have a part finish with a down bend, because the part would then be stuck inside the machine. With a 2-axis manipulator, that is not a concern.”

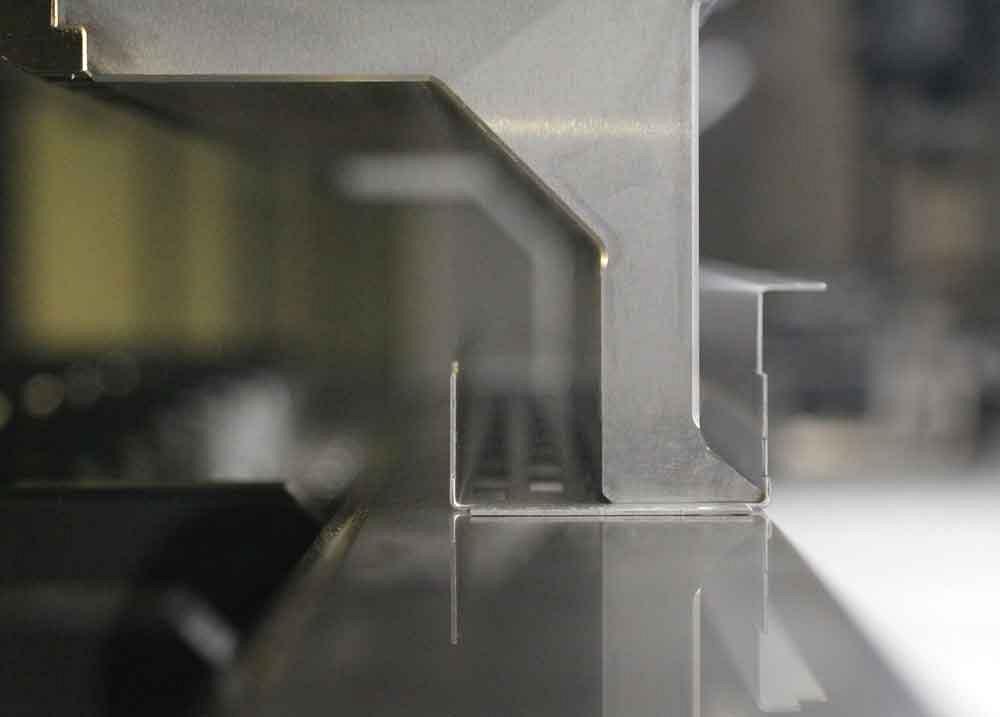

Another challenge for many panel benders is the forming of narrow channels. Because of the force required of the blank holders that hold the sheet down as a bend is completed, a certain minimum amount of flat material has to be clamped during bending.

“If your part gets too narrow, the blank holders are too large to hold onto the part anywhere,” said Bailey. “So, although in theory these narrow channels are an ideal application for a panel bender, generally it is difficult for machines to achieve these bends because of how they are designed.”

TRUMPF’s bender includes an auxiliary set of blank holders that have a smaller profile and can be moved into position automatically when a narrow profile is necessary.

Bailey points to doors and frames as examples of parts that might be ideally suited for the particular benefits of the panel bender the company offers.

“It could be the door and frame of an electrical cabinet, or it could be a door and frame for a building,” he said. “Regardless, they always consist of large panels and small channels. If you can do both, you have an ideal application for a panel bender.”

Although the company is working on a fully automated version of its panel bender, Bailey noted that the addition of an automated system doesn’t negate the value of a model with a manual positioner.

“Once you go to a system with automatic part rotation, you introduce limitations on geometries, because now you have another mechanical manipulator that has to fit on the part to be able to rotate it,” he explained. “Again, narrow profiles and down flanges become difficult to deal with.”

Prima Power’s panel benders range from a manually positioned model to a fully automated system. The Fast Bend, or FBe, is the company’s manually positioned model. As Paul Croft, bending product manager, Prima Power North America, explained, this model has become a go-to bender for special products.

“Because it doesn’t have a manipulator to move the part in and out, it allows us to bend certain geometries that couldn’t be made using the manipulator,” Croft said. “For instance, we can bend parts that are a couple of inches narrower because there isn’t a manipulator in the way. Also, because we use vacuum pads underneath the sheet to hold it in place and move it in and out of the bend, we can process parts with louvres in them, or that have a cutout in the middle.”

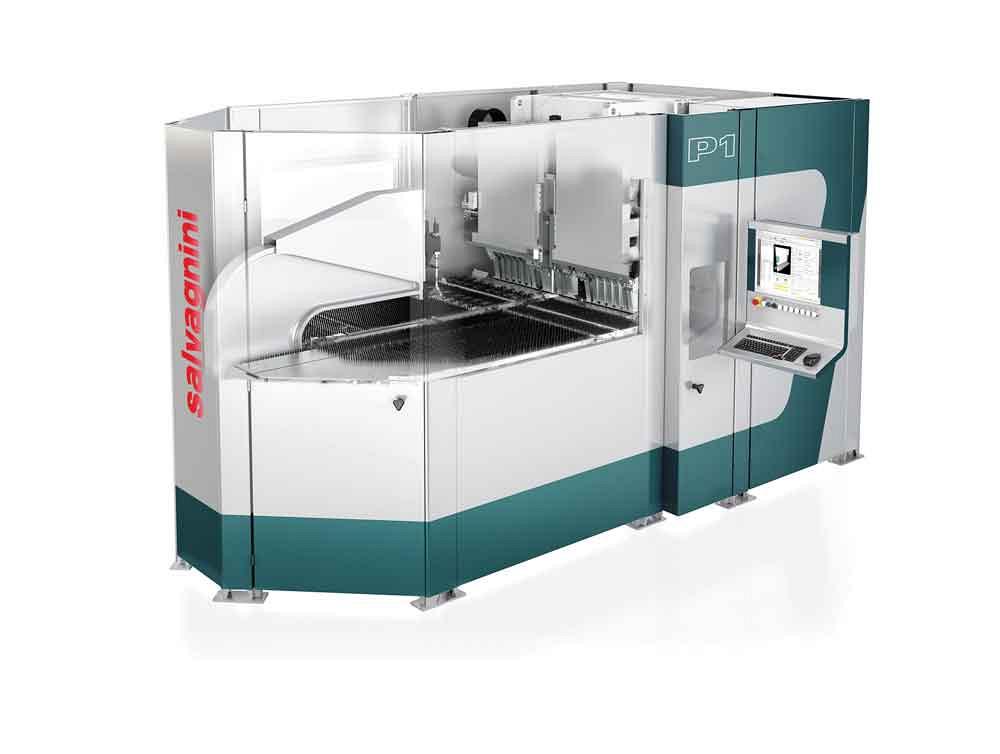

Salvagnini's P1 semi-automatic panel bender has proven popular for its small footprint and all-electric operating system. Photo courtesy of Salvagnini.

This bender also has two different modes: standard, in which the part is automatically fed during the bending sequence of every side, and press brake mode, in which the sheet is moved manually bend by bend, which is useful for very narrow profiles.

Like the TruBend, the FBe gives a company flexibility to run complex parts that have special requirements that would be difficult to manage on a fully automated system.

Semi-automated Options

Formerly, one of the main advantages of manually positioned benders was that they allowed single-piece flow. This is useful for kitting work – you can run a left-hand panel, a right-hand panel, the top to an assembly, and so forth, and everything is collected at the end in one kit ready to go to welding. There is an 8-second tool change between each part, but that is still much faster than a press brake. While manually positioned benders are still effective in this respect, a lot of shops that do kitting are drawn to semi-automatic panel benders if a manipulator isn’t an issue.

The semi-automatic panel benders on the market require an operator to place the part in the machine. From that point, a manipulator takes hold of the part and processes it completely. The operator then simply removes the part and follows the same process again.

Salvagnini refers to its semi-automated models as its Performer series. These are made available in three standard sizes, encompassing bending parts from 4 ft. long to 8 ft. long.

“These machines aren’t customized to the needs of each customer,” said Bossard. “We equip them with a series of features that are already pre-engineered and can be selected however the customer would like to put them.”

If you have been to FABTECH at any time in the past six years, no doubt you have seen Salvagnini’s P1 or P2 model churning out parts. The parts are loaded manually, but once the part is on the table, the machine takes over. In the past five years, all of the Performer series machines have been upgraded to include automatic thickness measurement, angle control, automatic setup, and automatic blank holder adjustment. Bossard said the series has proven popular for kit sequence manufacturing, which might include single-piece part flow of as many as 10 pieces that would go to welding assembly afterward.

The P1 is distinct in that it is a fully electric machine. For this reason, it can bend sheet only to a maximum of 16 ga. All other Salvagnini machines (and those of its competitors) bend sheet up to 1/8 in.

Prima Power's BCe Smart semi-automated panel bender is designed with fewer options to lower the cost of the machine, thus attracting potential users put off by the high cost of fully automated panel benders. Photo courtesy of Prima Power.

When the P1 was first released a few years ago, it did not include automatic setup, which meant it required about a 5-minute setup time between one type of part and another. This detracted from its value for kit manufacturing. The addition of this capability has automatically made it more valuable to shops. The P1 can handle sheet up to 62 in. by 39 in., with a maximum bend length of 49 in. and bend height of 5 in.

The P1 also now allows for a “last bend down.”

“The last bend down creates the requirement to have an additional safety circuit to protect the operator when he reaches in to remove that piece,” Bossard explained. “That has been available on our other machines for several years, but the specific safety circuit has now been designed such that we can include it on the P1.”

The P2lean can handle sheet up to 98 in. by 62.9 in., bend length of 85.82 in., and height of 6.49 in.

Both machines are ideal for kitted manufacturing. The challenge, of course, is that you still require one operator per machine.

“Even with a part with 16 bends in it, the machine is going to spit that part out in less than a minute,” noted Bossard.

Prima has two models in this semi-automated line, the BCe and BCe Smart. As Croft explained, these machines have the processing speed of a fully automated bender, but with the ability to do a single piece or kitted assembly.

“What it really boils down to is production requirements,” Croft said. “Arguably, you could purchase two BCe benders for the price of one of our fully-automated EBe panel bending systems. The EBe is really designed to be included in a full automation cell, whereas the BCe and BCe Smart machines are designed to be stand-alone units.”

The BCe Smart is Prima’s newest foray into the panel bending market, and it was really designed to bring the price down for customers. With those design demands, some basic limitations have been put on this model.

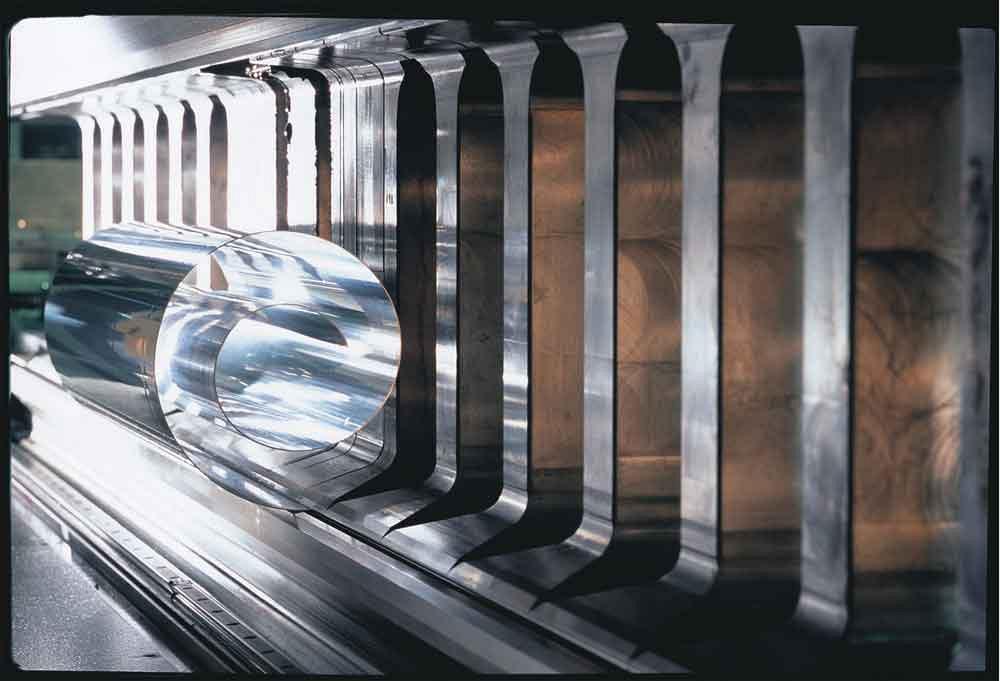

The main benefit of a panel bender is its ability to form complex shapes quickly and accurately. Here a spiral shape is being bent on a Salvagnini machine. Photo courtesy of Salvagnini.

“Generally, we find that the majority of the market doesn’t need any more than 80 in. of bending,” said Croft. “It is the only machine that is one-size-fits-all to keep it at a reasonable price point. Other machines that we make can go up to 140+ in.”

The other difference between the BCe and the BCe Smart is in the loading/unloading. The BCe is a fully-enclosed unit that runs a part into the enclosure, processes it, and rolls it out once it is processed. The BCe Smart has a smaller footprint. The operator places the part directly below the manipulator, which then takes the part and processes it. An LED reference bar helps the operator pre-center the part. Safety for the operator is provided by a laser light guard. When the part is processed, the operator can simply reach in and remove it from the table.

Again, this type of machine is ideal for kitted parts.

“With this machine you have an average of a 10-second tool change between different parts,” said Croft. “If I have a part that has a 40-second cycle time, I am only adding 6 to 10 seconds to process a single part. That tool change could have taken 10+ minutes on a press brake, so if I’m still only at 50 seconds while able to run a one-piece flow, a lot of people can live with that. It is still going to be the most efficient machine you have if you want to do 50 or 500 parts at a time.”

Fully Automated Benders

The limitation for all of the semi-automated systems discussed previously is that none of them can be equipped for integration in a fully automated production line.

“If you had our EBe panel bender as a stand-alone system, you could throw a stack of 100 parts on the left-hand side of the machine and it would spit them out as completed parts at the end,” said Croft. “But the benefit of that particular system is that it can be automated even further with one of our larger systems. It could be combined with a laser or shear or a blanking machine, and with robotic automation for sorting and stacking.”

Croft emphasized that although the EBe can be sold as a stand-alone machine, it is really most efficient when it is part of a larger automated cell. “The fact that it can be incorporated into any number of larger-scale systems is the biggest upside,” he said. “The EBe can be made in 133 in. and 147 in.; those larger sizes wouldn’t make much sense in a manually loaded machine where the operator has to handle parts. That’s how it proves its worth on a shop floor – rapid part production without operator interference.”

The models and special tooling can vary more substantially than the semi-automated options. For instance, there are eight models in Salvagnini’s P4 line of machines. Two of these models include flange, or open, heights of 10 in. Panel benders usually have a maximum open height of 8 in. which is another limitation in the type of parts that can be processed on a panel bender. Gradually, however, the limitations are shifting.

The two new machines with the larger open heights have maximum bend lengths of 88 in. and 122 in. Bossard suggested that the 88-in. model is ideal for electrical box manufacturing, because electrical boxes have tall sides.

“It is also ideal for people making drawers for workbenches, and food service environments,” said Bossard. “The 122-in. machine is particularly good for transformer cabinets, which are made of heavy material like 14-ga. stainless.”

The point is that these more sophisticated machines can be adapted to the needs of particular industries.

Growing Sophistication

Panel benders are an attractive product because they can do so much without human interaction, and the companies that make them are doing what they can to increase their sophistication to give users peace of mind in their operations.

For instance, Salvagnini has changed the drive systems on its panel benders to run on electric actuators. Other than the P1, which is an all-electric machine, its machines now use fluid power for the clamping of the part and the actuation of the bending blades. Everything else on the machines is electric.

“The use of fluid power is very effective for low-speed, high-torque actions, and that is what we are doing,” said Bossard. The elimination of large hydraulic tanks, pumps, and motors means less maintenance.

But as Bossard explained many other innovations are making panel benders efficient and effective for metal fabricators.

“For instance, we are using an eddy current device to confirm whether the correct material has been introduced in the machine,” said Bossard. “It will differentiate among aluminum, carbon, and stainless steel, just in case an operator is careless. And our machines measure the thickness of every piece of material that goes into the machine because thickness is the greatest variant to angle.

“We are also close to releasing some angle correction technology that accounts for mechanical property differentials,” Bossard continued.

Panel bending options have expanded in the past few years. If you have the type of complex parts that suit such a machine, you have much to consider – the size of parts, automation, and flange height requirements are just three issues.

Editor Robert Colman can be reached at rcolman@canadianfabweld.com.

Prima Power Canada Ltd., 224-210-9079, www.primapower.com

Salvagnini Canada, 905-361-8709, www.salvagnini.com

TRUMPF, 905-363-3529, www.us.trumpf.com

About the Author

Rob Colman

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

905-235-0471

Robert Colman has worked as a writer and editor for more than 25 years, covering the needs of a variety of trades. He has been dedicated to the metalworking industry for the past 13 years, serving as editor for Metalworking Production & Purchasing (MP&P) and, since January 2016, the editor of Canadian Fabricating & Welding. He graduated with a B.A. degree from McGill University and a Master’s degree from UBC.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

CWB Group launches full-cycle assessment and training program

Achieving success with mechanized plasma cutting

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

Welding system features four advanced MIG/MAG WeldModes

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI