- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Gliding Into New Markets

MacKenzie Atlantic Adds Medical Device Manufacturing to Precision Machining

- By Sue Roberts

- April 13, 2017

- Article

- Made In Canada

Matthew MacKenzie, CEO and president of MacKenzie Atlantic in Musquodoboit Harbour, Nova Scotia, and inventor of the Paraglide™, attaches the repositioning device to the back of a wheelchair. Additive manufacturing was used to produce prototype components before final designs moved on to machining.

According to Matthew MacKenzie, the secret to success for MacKenzie Atlantic is no secret. Everyone at the precision machining shop and its new fabricating division works as part of a highly skilled team that extends beyond the company walls. Each employee assists, supports, and provides manufacturing expertise to each customer. In essence, the MacKenzie Atlantic team becomes an integral part of its customers’ teams, working with them at every stage of product development. They recommend improvements and identify opportunities to reduce costs from design through delivery.

“We try to be an extension of our customers. When we get a drawing packet, we typically go through, scrutinize every drawing, and provide feedback. We’ll tell them that if they do this or that, they can make a part simpler, more cost-effective, get the part sooner, and have a more reliable product. We pride ourselves on that kind of relationship building, and those relationships have grown the company,” said MacKenzie, company CEO and president.

A combination of seasoned tradespeople and individuals in the early years of their industry careers perform what MacKenzie calls a cross between a trade and an art. “From people in management to operators to apprentices honing their skills, each person contributes to our growth. They are ambitious, dependable, creative, collaborative, and insanely attentive to detail.”

As a self-proclaimed A-type personality, MacKenzie applies a system and process to get any task done properly. It works.

Precision Led to Rapid Growth

MacKenzie had worked in the machining trade for about eight years when he decided to establish his own business. In 2006 MacKenzie Atlantic was incorporated as a one-man shop. It had two machines.

Fast-forward to 2017. Over 20 employees work two shifts in two MacKenzie Atlantic Nova Scotia facilities. The combined shops, one in Musquodoboit Harbour and one in Dartmouth, span over 23,000 sq. ft. The company has earned ISO 9001:2008, Canada’s Controlled Goods Program, and NATO certifications.

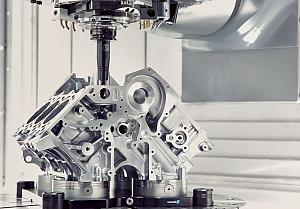

More than a dozen CNC machines, a full suite of fabricating and welding equipment, and a state-of-the-art electronic data collection system are part of the clean, lean operations. Positioning accuracy of ±0.0002 in., machining up to 12,000 RPM, and turning of components up to 26 in. diameter are accomplished on multiaxis turning and milling equipment and 3- and 4-axis mills. Fabricating capabilities, including welding, bending, and plasma cutting, were added in 2015.

“We work with some complicated machines, most of them 4-axis mills,” MacKenzie said. “We also have live-tooling lathes with subspindles and multifunctioning lathes with milling capabilities. We can put a billet of aluminum or steel in the machine and it comes out a finished part.

“We try to handle a part only once so we can provide a better-quality part and minimize setups. That helps push us towards higher-volume manufacturing.” Higher volume is anything over 1,000 units, but orders up to 60,000 over a 12-month period are not uncommon.

“Everything falls under an established process. We have a fully integrated ERP system. It is managed from the office; however, all of the employees on the floor have computers at the workstations with system access. They have access to all the drawings for a job, the parts database with setup sheets, product information and history, and any challenges we may have had,” he said. “All of our jigs and fixtures are tracked in inventory control so when we get a repeat order, they can be quickly located.”

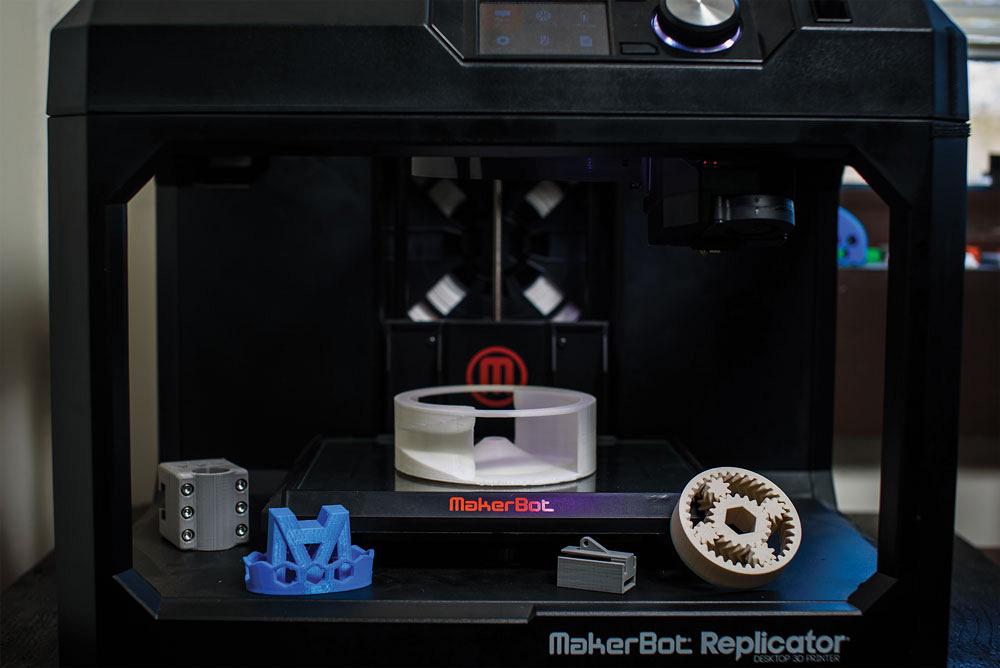

Additive manufacturing was added to the company’s capabilities to assist with Paraglide prototype components, but it quickly became an important part of many machining processes.

The E2 Shop System software tracks the projects of both facilities so everyone in the company can find information on anything that happens with an order and notifications of any project changes. Tens of thousands of part numbers reside in the system so far.Customers, almost exclusively domestic, represent the marine, aerospace, military, oil and gas, and medical industries.

“We produce parts for a lot of environmental-type equipment, and our certifications allow us to do on-site ship repair. We are one of the few companies approved to work with Irving Shipbuilding on the FELEX program, which is the retrofit of our current frigates. We’ve been doing work on the radar platforms for the past five years,” said MacKenzie.

Collaboration Sparked Invention

A second company, MacKenzie Healthcare Technologies, is in its infancy. MacKenzie Atlantic’s association with Nova Scotia Community College (NSCC), and NSCC’s relationship with Northwood, a not-for-profit continuing care facility in Halifax, led to its inception.

“About five years ago NSCC approached me and said that Northwood had provided the college with a list of voids in the long-term-care market in hopes that technology might help. The first item on the list was something to help reposition people who slide forward in their wheelchairs and can’t adjust themselves,” said MacKenzie.

The students in NSCC’s mechanical engineering program devised a system comprising a sheet under the person in the wheelchair, which attached to a belt worn by the caregiver during repositioning. When attached to the sheet, the belt allowed the caregiver to use his or her body weight to pull the person back to a comfortable position. Northwood said that the device helped and wanted to implement its use throughout the facility.

Since the educational institution could not provide manufacturing, NSCC turned to MacKenzie Atlantic with a licensing offer. “I liked the idea and concept,” said MacKenzie, “so we bought the licensing agreement and fine-tuned the device over about six months.”

After a trial of the fine-tuned device at Northwood, there were some areas of concern. Caregivers had to bend down to use the device; the belt seemed cumbersome; and the repositioning action could put pressure on the knees and back of the caregiver, leaving him or her open to musculoskeletal injury. Progress halted and the project spent about a year on the corner of MacKenzie’s desk.

“After parking the idea for a little while, I decided that we needed to develop an automated device to meet this need. We had to make it mechanical so no caregiver was needed and make it so the person in the chair could reposition himself or herself without assistance.”

With that mission in mind, MacKenzie Atlantic applied for and received the first of three grants from National Research Council Canada. Two were Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP) grants that contributed to the development of the product. The first grant was used to hire a recent graduate to assist with R&D and prototype production. The company began by building a full, working prototype based on MacKenzie’s idea to prove that the concept was viable and could be commercialized.

“We spent eight months or so proving that the concept would work and learned that we would need to build in enough flexibility to allow the device to be functional on different models of wheelchairs and sturdy enough to meet the demands of repositioning a person who weighs up to 300 pounds,” MacKenzie said.

AM Sped Product Development

He also discovered that fine-tuning the brackets for the device was an ongoing job that required going back to the drawing board to redesign and produce several different prototype components. That led to the addition of MakerBot 3-D printing technology to the Musquodoboit Harbour shop floor to build prototypes from ABS plastics.

“We found that we were going through so much product development—changing our minds about how the brackets or housing should work, or how all the internal components should fit in the housing—that it wasn’t practical to machine each part every time we made a change. Our investment in the printer really changed the game. We were able to design and prototype significantly quicker.

“I didn’t realize how powerful additive manufacturing was in an environment like ours until we had it. We would design a new bracket in the morning and by the end of the shift the printed versions would be in my hand.”

Paraglide™ automated wheelchair repositioning device, the result of all that R&D, will be available this summer. MacKenzie turned to Enginuity, a Halifax engineering firm, to refine the mechanical design and create customized electronics boards that meet regulatory requirements for automated medical devices.

The final design incorporates the original concept of a specialized sheet under the wheelchair-bound person, but a mechanical device, operated by a Bluetooth remote control, winds the sheet to slide the person back into an upright position. The device then unwinds, allowing the sheet to travel with the person’s movements as they shift throughout the day. The individual in the wheelchair can use the remote to reposition at will, for comfort or to prevent costly and painful ulcers, or a caregiver can operate the Paraglide without the risk of personal injury from lifting.

During development, MacKenzie’s Paraglide concept won the 2016 BioInnovation Challenge, a Maritime-wide competition created by BioNova, Nova Scotia’s life sciences industry association. The award included $15,000 in seed funding and $30,000 worth of advisory services to assist with getting the product to market. Evaluation criteria included product adaptability, market pull, and consumer readiness.

“In our presentation at the BioInnovation Challenge we talked about how many units we expected to sell and were told that our estimates were too low. We’ve secured patents in Canada and the United States, and we are finalizing an international patent,” said MacKenzie. “We have interest from health care distributors in the U.S. and we’re already looking at exports.”

MacKenzie’s initial strategic plan was to launch the Paraglide in Nova Scotia as an incubator idea, get feedback, adjust if needed, then market across Canada. Market demand, however, put the product on the fast track. “A lot of people are trying to get their hands on Paraglide, but we need to make sure it is right when we launch this summer.”

Paraglide will be marketed through the newly established MacKenzie Healthcare Technologies. “Paraglide is just the start for the new company. We plan to build it around developing assistive devices specifically for long-term-care needs that aren’t being met. We want to meet those needs with technology that will help prevent injuries and restore dignity.”

Printing Also Serves Machining

The additive manufacturing capabilities quickly took hold throughout the plant. MacKenzie said that even the guys on the shop floor who are not directly involved in product development have incorporated AM into their work flow. It’s made the machining side of production more effective.

“They machine very complicated parts for aerospace and defence all the time. Now they 3-D print full-size models before they go to machining. They can have the part in their hands, look at it, feel it, and make sure all the tooling they select to machine it will have enough clearance,” he said. “And while the programmers are working on a complex part, they often print a prototype to sit on their desk, especially if there are difficult angles. They can hold the part and physically line up the end mill to verify its selection.

“Even though it is another process, it saves time. They can set the printer up to run overnight and have the part completed and ready for them in the morning.”

Engineering companies on the customer roster are also taking advantage of the process for prototypes. “We tell them that if a printed part will work to verify form, fit, and function, we can have it in their hands by tomorrow. Oftentimes they will email back with the print, get the part to be checked, and the next week we get an order for 50 or 100 of the machined parts. It’s a weeklong process instead of the three or four weeks it could take if we were machining the prototypes.”

Managing the Future

The question now is, What’s next? With the addition of producing Paraglide components for the health care device company, significant growth is expected over the next five years. One company will feed the other. But that growth, as well as adding customers for the machining and fabricating services, will be carefully handled.

“We’ve thought about marketing our services to the U.S. but haven’t capitalized on that yet because I believe in controlled growth. We don’t want to lose sight of how we act as an extension of each of our customers who give us opportunities and rely on us to deliver.

“Finding a right new opportunity is a team decision. We have strategic meetings to talk through what a contract will mean for MacKenzie Atlantic and how we are going to mitigate the risk to us and our current customers. Would a new contract mean adding more equipment? Or more people?

“It has to be the right fit for us, and we have to be the right fit for them.”

Photos by Ash+Rich, Applehead Studio.

MacKenzie Atlantic, 902-889-3047, www.mackenzieatlantic.com

MacKenzie Healthcare Technologies, 902-880-1836, www.mackenziehealthcaretech.com

About the Author

Sue Roberts

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8241

Sue Roberts, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. A metalworking industry veteran, she has contributed to marketing communications efforts and written B2B articles for the metal forming and fabricating, agriculture, food, financial, and regional tourism industries.

Roberts is a Northern Illinois University journalism graduate.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Industry Events

ZEISS Quality Innovation Days 2024

- April 15 - 19, 2024

Tube 2024

- April 15 - 19, 2024

- Düsseldorf, Germany

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada