Founder

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Create Operational Excellence in High-Variety Environments

Use the pull of the customer to create a flexible flow of a mix of parts

- By Kevin J. Duggan

- February 22, 2017

- Article

- Management

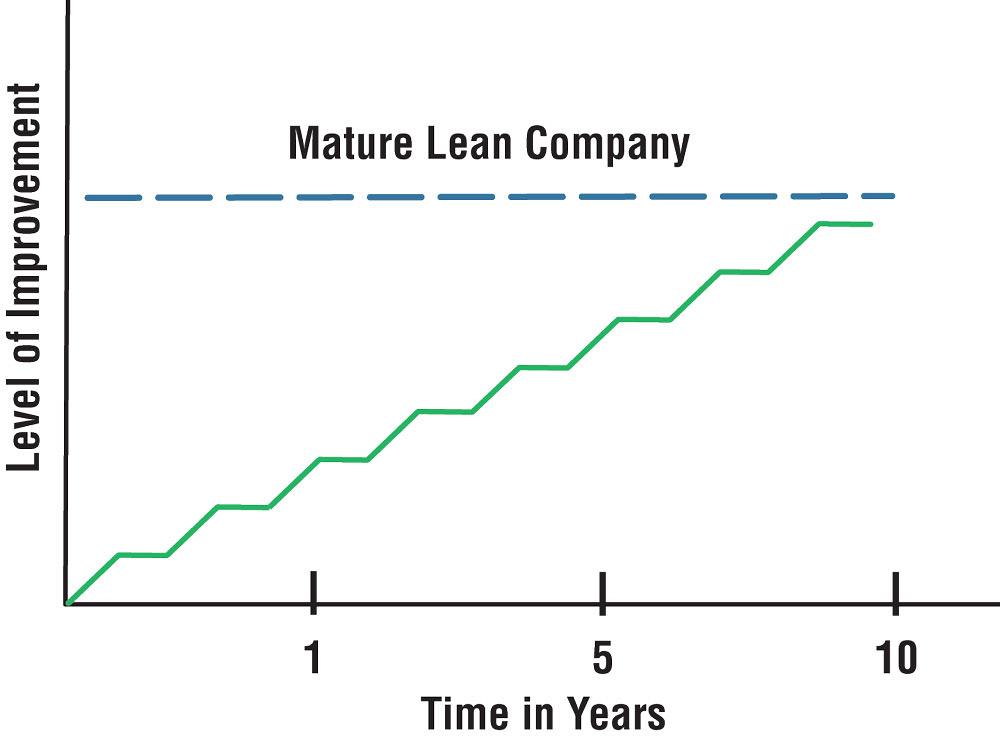

Figure 1--The staircase of continuous improvement indicates where improvements are made and then sustained in an ongoing and never-ending journey.

Most manufacturing operations have used lean principles to eliminate waste and drive efficiency improvements, the target being to reduce inventory, lead time or cost, or improve quality. The process typically starts with company leadership setting an improvement goal in an area of the operation.

Teams then apply lean tools to achieve the goal, then sustain the gains by creating standard work, monitoring, and measuring procedures. This process is then applied to another area of the operation: Management sets another goal, teams use lean tools to achieve it, and then sustain the gains via standard work. This process of improvement does yield results over time. However, the results are incremental, and over time the best this method of improvement can do--if the operation doesn’t slide backward at all--is yield a slow, steady climb up the staircase of continuous improvement (see Figure 1).

However, instead of taking years and achieving incremental improvements, some companies have jumped the performance of their operations in a year, and even in months. How? By setting a destination of operational excellence and following the process to achieve it, even in high-mix, high-variety environments.

Defining Operational Excellence

The destination of operational excellence is defined as “When each and every employee can see the flow of value to the customer, and fix that flow before it breaks down.”SM Operational excellence is not just flow, but self-healing, autonomous flow – a flow that delivers the product seamlessly day in and day out, without the need for management intervention.

Here’s how it works: The goal in operational excellence is to first create flow through all areas of the organization and make the flow visual so anyone, even visitors, can follow the flow from beginning to end and understand if it is normal and on time or abnormal and behind, without asking any questions. Once this is achieved, the flow can then become self-healing, meaning the employees who work directly in the flow are able to identify and fix flow problems on their own, without management intervention. And when leadership no longer spends its time fixing the flow, it can focus full time on offense, or the activities that generate business growth.

While this state may seem difficult to attain, organizations are able to achieve operational excellence by following eight principles1:

- Design lean value streams.

- Make lean value streams flow.

- Make flow visual.

- Create standard work for abnormal flow.

- Make abnormal flow visual.

- Create standard work for abnormal flow.

- Have employees in the flow improve the flow.

- Perform offense activities.

The first principle of operational excellence sets the stage for working through the others and is crucial to successfully implementing operational excellence companywide. Within the first principle, the following sets of guidelines are used to create flow through all areas of the organization:

- Eight guidelines for end-to-end value stream design

- Ten guidelines for the mixed-model pacemaker (the point at which an operation schedules the value stream)

- Six guidelines for shared resources flow

- Nine guidelines for office flow

- Seven guidelines for supply chain flow

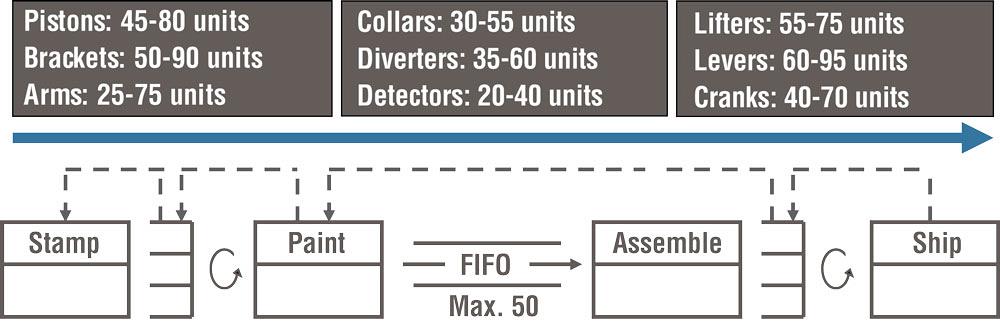

When value streams are required to produce a high variety of products, it can bring many challenges. The different processing times, fabrication steps, and raw materials required to produce a mix of products down the same value stream often results in choppy or unpredictable flow, and this irregularity in flow can make operational excellence difficult to achieve and sustain (see Figure 2).

To create operational excellence in complex operations that produce a high variety of products, the 10 guidelines for mixed-model production are key. By applying these guidelines, operations can design value streams capable of producing a mix of products or product variations at the pull of the customer.

Creating Mixed-Model Value Streams to Support OpEx

To create mixed-model value streams that support operational excellence, a manufacturer starts an operation by creating product families, or groups of products that have similar process flow and work content. The next step is to create one current-state map per product family and then a future-state design for that family that can achieve operational excellence.

Figure 2--Flowing a mix of parts through the same value stream can be challenging, especially when the parts have different processing times and levels of demand.

Following this process for low-variety product families is relatively straightforward, but creating operational excellence for high-variety product families can be difficult, which is why the 10 guidelines for mixed model production are used2. They are:

- Do you have the right product families? Create product families based on similar processing steps and work content, not brainstorming.

- What is the takt time at the pacemaker? Determine how often the pacemaker must produce a part to keep up with customer demand for the product family.

- Can the equipment support takt time? Determine if existing machine capacity can support the product family within the established [ital]takt time.

- What is the interval? Calculate how often the pacemaker will cycle through and produce all the parts in the product family.

- What are the balance charts for the products? Balance the work content, per operator, to [ital]takt time to create continuous flow through the pacemaker process. There will be different balance profiles for each product within the family.

- How will we balance flow for the mix? Determine how variation within customer demand and the product family will be handled, either by adjusting labour, sequencing, or work balancing.

- How will we create standard work for the mix? Standard work means establishing one standard way to build the products in the family, and then having everyone follow that method.

- How will we create pitch at the pacemaker? Pitch is a visual time frame that tells everyone in the value stream if they are on time to customer demand. The pitch created is tied to how often work is released to and taken away from the pacemaker.

- How will we schedule the mix at the pacemaker? Determine the mix that can be supported at the pacemaker, and schedule the pacemaker to handle variation within the product family.

- How do we deal with changes in customer demand? Customer demand can vary, and we need to pre-establish a Plan B to use when it does. Plan B might involve pulling a product or rebalancing the pacemaker.

While all 10 guidelines are essential to create mixed-model value streams that support operational excellence, establishing an interval at the pacemaker (No. 4) is key and can be particularly difficult in high-variety environments. As a result, it requires a closer look.

Establishing an Interval at the Pacemaker

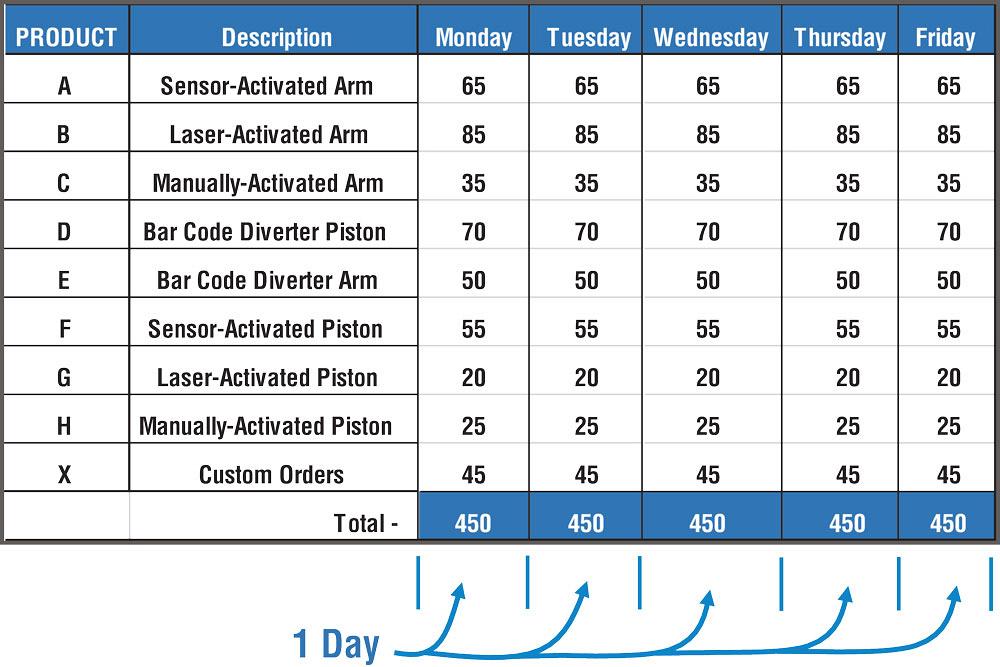

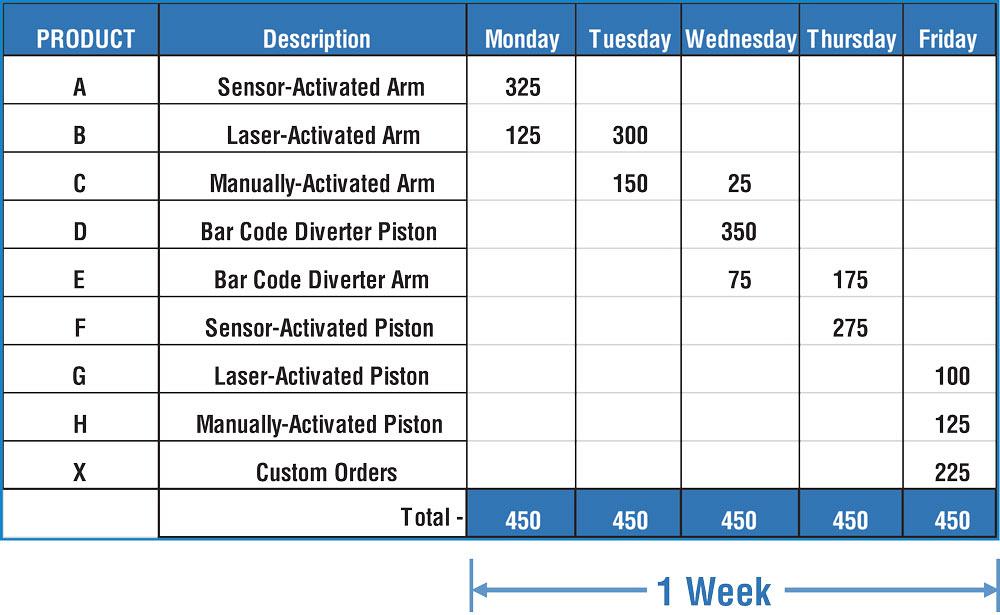

The interval refers to how frequently the pacemaker can cycle through all the parts in the product family. If it takes one week to cycle through all the parts in the product family, then the interval is one week (see Figure 3).

If the pacemaker takes one day to make all the parts in the product family, then the interval is one day (see Figure 4).

The length of the interval is tied to many aspects of the operation: lot size, lead time, how frequently defects are caught, and more. Therefore, lowering the interval improves these metrics. For example, with a one-week interval, parts are made once per week, meaning quality issues can be identified only once per week, and an operation would have a week’s worth of production to rework or scrap. However, if the interval were one day instead of one week, then only a day’s worth of parts would need to be scrapped.

The same is true for lead time. A one-week interval means the lead time is one week, but if the interval is reduced to one day, then the lead time also becomes one day, thereby yielding an instant competitive advantage. The interval is the link between scheduling the pacemaker and meeting changing customer demand, or demand for new customers. In other words, the smaller the interval, the better an operation can meet changing customer demand, and the better the opportunity to capture new business and increase market share.

And since in high-mix production smaller intervals require more setups, the focus then becomes being really good at setups. Having predictable setup times by using standard work is key, and a good way to do this is through education on how setups and interval work bring in new business.

Using High-Variety Value Streams to Leverage Growth

The end result of applying the 10 guidelines for mixed production to high-variety operations is the ability to flow a mix of parts with different cycle times and levels of customer demand down the same value stream, all at the pull of the customer. With the first principle of operational excellence complete, the remaining principles can be applied to create autonomous, self-healing flow throughout the organization that does not require management intervention, even when things go wrong.

With operational excellence, managers are now able to focus fully on business growth: working more closely with product development, visiting customers to understand how the operation can better support their needs, and incorporating operations into the top of the innovation funnel. And that is exactly how operations can improve their market share and growth.

Kevin J. Duggan is the founder of the Institute for Operational Excellence and Duggan Associates, 401-667-7299, www.dugganinc.com.

Figure 3--At a volume of 450 per day, an operation builds each product in sequence and changes over when each lot is done. In this case, it takes one week to cycle through each part number in the family.

Notes

1 Kevin J. Duggan, Design for Operational Excellence: A Breakthrough Strategy for Business Growth (New York: McGraw-Hill), 2011.

2 Duggan, Creating Mixed Model Value Streams: Practical Lean Techniques for Building to Demand, 2nd Edition (New York: Productivity Press), 2013.About the Author

Kevin J. Duggan

401-667-7299

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

BlueForge Alliance partners with Nuts, Bolts & Thingamajigs to develop Submarine Manufacturing Camps

Portable system becomes hot tech in heat treatment

Orbital tube welding webinar to be held April 23

Cidan Machinery Metal Expo 2024 to be held in Georgia May 1-2

Corrosion-inhibiting coating can be peeled off after use

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI