Associate Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Doing it right the first time

A look at how in-process inspection makes machining good parts easy.

- By Lindsay Luminoso

- January 18, 2016

- Article

- Measurement

In today’s manufacturing environment, time is money. Manufacturers are constantly worried about cycle time, meeting tolerances, and getting the parts to the customers. The traditional relationship between machining and inspection is changing to adapt to meet the ever-growing needs of the manufacturing process. Customers are only paying for good parts, so it is important to get it right the first time. Parts that are machined incorrectly, have features out of specification, or missing completely, can mean that materials are scrapped and time is lost making a new part, all which negatively affects the bottom line. In-process inspection is one way to ensure that a part is being machined correctly the first time.

“The traditional relationship between machining and inspection is that machining is completed first, and the component is then transferred to a dedicated piece of inspection equipment to be approved or rejected,” explains Brett Hopkins, North America manager of Delcam Professional Services. “However, as machining techniques become more sophisticated, and as components become larger and more complex, there are a growing number of cases where closer integration is required to give higher productivity and reduced wastage.”

When it comes to large, expensive workpieces, the last thing any operator wants to find out is that the part they’ve spent the last couple hours machining is out of specification. In the manufacturing process, checks can be put in place to ensure that the part continues to be made correctly.

“It is so important to do in-process checks, and be able to catch any process variations or issue as quickly as possible,” says David Chang, technical sales manager (Measurement & Automation Products) for Renishaw.

If a part is incorrect and the error is not caught until a post-process inspection, oftentimes it is too late and the entire thing needs to be scrapped. What is worse, additional parts may incur the same error before the operator is able to catch and correct the problem.

“During any machining, mistakes can be made due to operator error, tooling wear, thermal issues—inspection is imperative to ensure the error is caught early or not repeated,” adds Scott Warner, Canadian regional manager for Heidenhain.

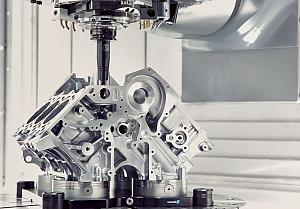

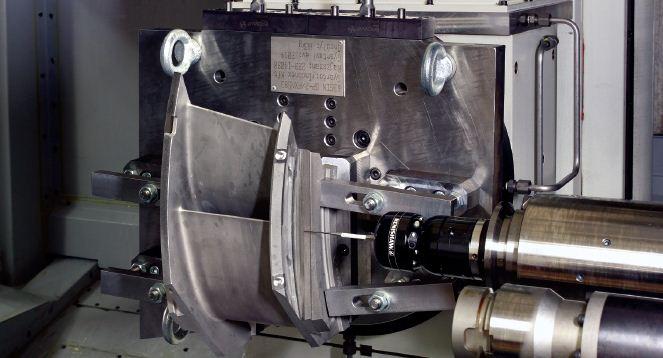

One way that in-process inspection can be done is through machine tool probes, which ensure that key features on the workpiece are correct to allow the machine to continue the machining process. One of the greatest advantages of the machine tool probe is that it allows for verification to take place on the machine without having to remove the workpiece.

This can be beneficial if you are working with a large or heavy workpiece.

“For example, let’s say you have a 500 kg part that is taken off the machine and brought into an inspection lab,” says Philip Smith, technical sales manager for Renishaw. “If they find there is a problem, the part then needs to be taken back and put into the machine. And if it can be, then it needs to be reworked. For a lot of specific jobs, you may only get one shot at it.”

If the part is inspected and is out of specification, the amount of time it takes to remove the part, wait for the part to acclimatize to the lab, inspect the part, and fixture the part back on the machine, can be costly. Not to mention that it is almost impossible to re-fixture the part in exactly the same position.

On-machine verification can ensure that a critical feature is machined within specification before any additional processes are started.

“In process inspection saves repeating cycles of machining and inspection, interspersed with long set-up times on the respective pieces of equipment,” explains Mary Shaw, Delcam Marketing Manager.

“Depending on the complexity of the part and the size, the overall production gains can be very significant, anywhere from hours to days, saving time and money on overall manufacturing costs.”

The main purpose of in-process inspection is to gauge the part and if a specific dimension changes, determine what part of the process has changed.

“This can be due to temperature, tool wear, or tool breakage,” explains Chang. “You want to catch that quickly.”

The part can be verified but other important elements are also assessed to ensure a productive process. These assessments allow for decisions to be made immediately as to whether or not the process can be continued or parts should be scrapped. It also allows for process variations to be corrected based on generated reports.

For example, tool breakage on the shop floor can be assessed accurately and a decision made immediately to determine whether the part can still be completed within tolerance or whether it will have to be scrapped.

One of the challenges, when it comes to using machine tool probes for verification, is that you are not getting a true inspection of the part. Both Chang and Smith stress the importance of understanding the total production process before going forward.

You have to start at the process foundation, the machine itself, and get to know the parameters of the machine tool before entering into the world of in-process inspection.

“We don’t call it on-machine inspection. We can’t really say it’s inspection because you can’t use the machine that is machining the part to inspect the part,” explains Smith

It’s really more about verifying that the part is correct and features are accurate. However, before the verification process can occur, the machine needs to be functioning correctly.

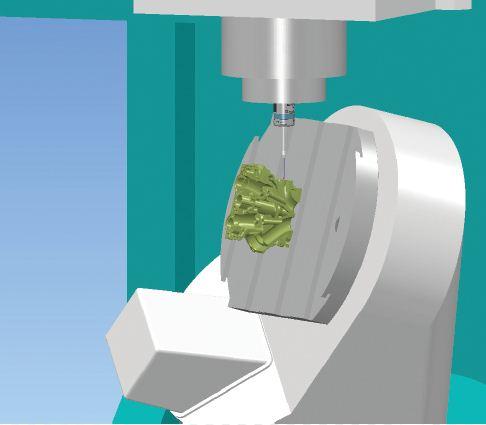

“That foundation is there. Once we know that the machine is working to within specification, then we use one of our probes in conjunction with software, we do a comparison of the actual part on the machine, and we compare that to a CAD model that has nominal values,” Smith continues.

One of the great advantages is that inspecting at the machine using touch probes on the machine allows a more immediate inspection. “However this can be dangerous as it is not an independent inspection, as the inspection is done on the same machine as the part was produced on. Errors associated with the machine will not show up on the inspection,” adds Warren.

This is why shops should get to know their machining process. Right from the process foundation with the machine through the process settings in order to understand how in-process inspection will work for you.

“Normal inspection in the quality department takes time and during this period the mistakes continue causing more rework and therefore [wasting] time and [money],”

says Warren.

The advantages of using in-process inspection are numerous. Manufacturers working with high-value, low volume parts can use machine tool probes to verify that features on a part are machined according to specification, allowing the part to continue through the manufacturing process.

Ensuring that a part is correct during the machining process can ensure that good parts reach the customer quickly and the manufacturer is not left with a ton of scrap.

“Cycle time is the amount of time it takes to make one good part. Customers don’t pay for bad parts. Not everyone thinks this way,” says Chang. A machine can be up and running all day long, pumping out hundreds of parts, but if there is even a little variation in the process, you can end up with a day’s worth of bad parts. And no one wants that.

About the Author

Lindsay Luminoso

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

Lindsay Luminoso, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. She worked as an associate editor/web editor, at Canadian Metalworking from 2014-2016 and was most recently an associate editor at Design Engineering.

Luminoso has a bachelor of arts from Carleton University, a bachelor of education from Ottawa University, and a graduate certificate in book, magazine, and digital publishing from Centennial College.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Industry Events

ZEISS Quality Innovation Days 2024

- April 15 - 19, 2024

Tube 2024

- April 15 - 19, 2024

- Düsseldorf, Germany

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada