- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Machine tools + turning

Taking a hard look at a niche process

- By Nate Hendley

- December 1, 2014

- Article

- Metalworking

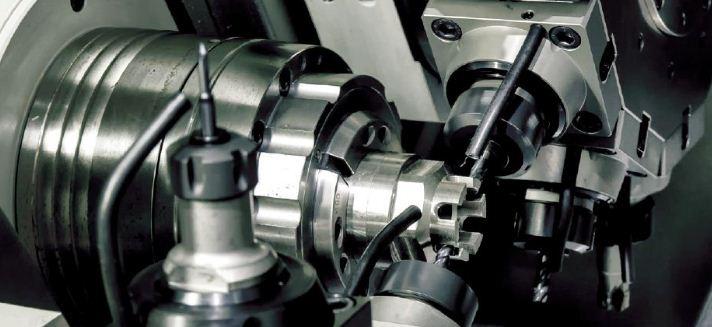

Robert Nefkens, managing director of Hembrug Machine Tools from the Netherlands, is a fervent believer in what many still consider a niche process. The process is hard turning—defined in Hembrug literature as “single point cutting of hardened part pieces [with hardness values] between 55 and 68 HRC.”

“Well, what I’ve noticed—people are getting more and more familiar with hard turning,” said Nefkens, interviewed at the Hembrug booth at Chicago’s recent International Manufacturing Technology Show (IMTS). The doctor’s English was shaky, which made it difficult for him to make his point. Hembrug corporate literature, on the other hand, comes in flawless English and a singular point-of-view. Hembrug operates two websites, a corporate site (which describes Hembrug as “the hard turning company”) and a separate site (found at www.hardturning.com) solely devoted to the glories of hard turning.

“In factories throughout the world, hard turning is replacing grinding, cutting costs and raising productivity,” boasts hardturning.com.

According to this site, hard turning offers several advantages over grinding, including greater accuracy, flexibility and productivity (hard turning is three to four times faster than cylindrical grinding). Multiple operations can be done in one set up (saving time and money) while the whole process is environmentally friendly (hard turning can be done ‘dry’), adds the site.

All very well, but Hembrug is still a relatively small fish in the machine tool market.

It’s important to ask, what do the big players think of hard turning?

As it stands, opinions range all over the map. Some industry experts think Hembrug is on to something, while others dismiss the Dutch firm as way off base.

“Anyone who thinks a turning center can be more accurate than a grinder must have used a seriously bad grinder … turning centers can be very accurate, but grinders are in a different category,” says David Fischer, lathe product specialist at Okuma America Corp. in Charlotte, North Carolina. “The grinder is a more robust platform when parts have to be held to millionths. I can run the grinder for days on end and never have to get fussy with the offsets to maintain size. Typically, a lathe will have to be constantly monitored and the offsets constantly adjusted.

“Finish is another area that can be an issue. A grinder will be consistent with finish where a turning center will change as the tool wears.” Fischer is willing to concede that, “hard turning does tend to be more environmentally friendly since you eliminate swarf disposal.” He also notes that “hard turning can be done on any of Okuma’s turning centers” including the new HJ-250E horizontal lathe with a FANUC control.

Still, Fischer can’t accept Hembrug’s premise that hard turning is the wave of the future.

“Progress continues to be made with hard turning and turning centers continue to improve in accuracy. That said, the most robust process is still a grinder and will be for the foreseeable future,” he says, adding that hard turning has been cited as a growing trend “for decades” and still hasn’t achieved widespread acceptance.

Tom Sheehy, manager of applications engineering at Hardinge, Inc., of Elmira, New York, takes a considerably different tack.

“Hardinge has been hard turning for over 20 years and has extensive process and cutting tool knowledge… additionally, Hardinge has been conducting hard turning seminars for 10 years or more, to assist our customers in getting up to speed in this area,” says Sheehy.

“Most customers that inquire to Hardinge in regards to hard turning are looking for faster throughput, accuracy, process and machine flexibility, reduction in set-up times as well as multiple operations in a single set-up, all of which reduce the cost of the finished component. The majority of hard turning is performed dry, resulting in decreased expense in coolant disposal … there can be a substantial cost savings from increased throughput via faster metal removal rates and decreased cost of equipment, when compared to grinding, while maintaining comparable tolerances and quality,” adds Sheehy.

He notes that Hardinge’s Super Precision series of CNC lathes, “are an ideal choice for hard turning due to the rigid structure of the machines, collet ready spindles and 0.1 micron control resolution offered on these models.”

Sheehy believes that many of the problems associated with hard turning should be blamed on the machinist, not the machine. Factors that can impede hard turning include lack of machine tool rigidity, lack of workholding rigidity, lack of tooling rigidity and lack of part rigidity.

Ignorance about the cutting theory behind hard turning and improper part preparation can also lead to failure.

Even when done properly, however, hard turning is not a perfect process.

“Hard turned surfaces can at times experience ‘white layer’ formations. This appears as a white layer at the surface of the material … this white layer cannot be seen by the naked eye,” says Sheehy. “Basically it is a very hard sub layer left on the surface and is often caused by incorrect cutting parameters. It is normally caused by severe plastic deformation that cause rapid material grain changes or surface phase transformation as a result of rapid heating and quenching of the surface.”

He does point out that white layers aren’t unique to hard turning, and sometimes show up in grinding applications as well. The danger is that the white layer flakes off and causes premature component failure.

Knowing what kind of inserts to use in hard turning is also vital.

“CBN (Cubic Boron Nitride) is the most predictable from a process standpoint for the majority of all applications and in the case of interrupted cutting,” says Sheehy.

“CBN tooling will also, in general, hold a tighter diametrical tolerance and produce a better surface finish. Ceramics and cermets are applicable to generally more open diametrical tolerance components and surface finishes, however typically will not work well in interrupted cutting applications. The major distinction when choosing one over the other is the actual application and usually comes down to cost. CBN is typically more expensive than ceramic and cermets by a factor of four. In the proper application, implementation and cutting parameters, ceramic or cermets can achieve similar cutting results as CBN at a lower cost.”

If Fischer is skeptical about hard turning and Sheehy is supportive, Michael Cope, product technical specialist at Hurco Companies Inc., in Indianapolis, Indiana, takes the middle-ground.

“As the technology of cutting tools advances each year, more and more shops are becoming aware of the benefits of hard turning. However, although it is definitely a growing trend in the industry, I don’t know that I believe that it will ever reach the level of ‘major trend.’ The overall need in the majority of shops just isn’t there,” says Cope.

He agrees with Hembrug’s list of hard turning advantages over grinding, with the exception of greater accuracy; “hard turning is just a different form of single-point turning and does not reach the accuracy level of grinding,” he says.

He echoes Sheehy’s position, that machinist inexperience is often to blame for hard turning difficulties.

“Machinists generally aren’t used to cutting materials that have been hardened to such levels before reaching the machining process. Without some guidance from people with experience and from tooling companies, it is very difficult to know what speeds or feeds to use, what cutter geometry is necessary, whether you need to use ceramic inserts or carbide, etc.,” says Cope.

“All Hurco turning centers are capable and well-suited for hard turning … people often think of Hurco as a mill builder, but we now have 16 different models of lathes, with the TM8i being the most popular,” he adds.

So, with all of this in mind, what of Hembrug’s boast, that hard turning is replacing grinding? Machine tool companies and manufacturing facilities alike weigh in.

“We hard turn most of the time and have for a number of years,” says Peter Alden, co-owner of Wessex Precision Machining of Ayr, Ontario.

“We used to have a cylindrical grinder but we got rid of it and now we just hard turn … I’m not sure [hard turning] will completely do away with grinding, but it will replace most of it.”

Cope disagrees. “I don’t believe that hard turning will ever replace grinding, because the accuracy just isn’t there. Although [hard turning] definitely has its place, the vast majority of parts and products simply don’t require it, because the parts don’t require heat-treating. Therefore, I believe that it will remain a popular niche application,” he says.

Unsurprisingly, Sheehy takes a vastly different viewpoint.

“Hard turning is replacing a lot of grinding applications … this is occurring in all industry segments that we participate in and we anticipate that hard turning will continue to evolve and grow as a whole across all industry segments. Currently, I would say that over 50 per cent of the projects that are submitted to Hardinge applications from our sales force are hard turning inquiries,” he says.

Back at IMTS, Nefkens chuckles at how hard turning has entered the popular consciousness.

“I remember when we were at [trade] shows 15-20 years ago. [People] almost got angry when we talked about hard turning. They said it was impossible. We had to explain it over and over again,” he says.

For advocates such as Nefkens, the fact hard turning can now be rationally discussed without tempers flaring is proof the process is slowly edging towards the mainstream.

About the Author

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI