Associate Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

A guide to bending safety

A press brake can be one of the most dangerous machines on the shop floor, but the latest safeguarding devices and best practices help keep operators safe

- By Lindsay Luminoso

- November 26, 2018

- Article

- Fabricating

With proper training and safeguarding devices, operators can perform bending operations with ease and without fear of injury.

A press brake is one of very few pieces of equipment on which an operator is required to directly interact with the machine. And with the ram outputting significant tonnage, this machine has the potential to be extremely dangerous. But with the proper training and safeguarding devices, operators can perform bending operations with ease and without fear of injury.

What to Watch out For

There are many hazards when it comes to bending operations. Most recognizable is where the punch and the die meet—the point of contact, or pinch point. If something other than the material being bent gets in between the punch and the die, you could be looking at a catastrophic accident.

“Operators really need to respect the machine they are in front of and understand how it works,” said Sean Mashinter, sales manager at Empire Machinery & Tools, Winnipeg.It’s not just the obvious areas that have the potential to be dangerous. That’s why understanding the machine’s capabilities and potential can make all the difference for safe operations.

“A less obvious area of injury occurs when bending a part with a flange,” said Scott Ottens, bending product manager at Amada America, Buena Park, Calif. “As the part bends, it swings up. In this scenario, it’s possible that you can trap your hand between the part and the upper beam. So it’s not just the tools but the part itself that has the potential for danger.”

Ottens also pointed out a less common hazard–a pinch injury with the backgauge. He explained that typically the backgauge moves in order to come into position for the next bend even without the pedal depressed. If a hand or arm was in or around the tools, it could get pinched.

The experts agreed that when it comes to tool changes, operators should be especially careful not to place their fingers or any part of their body between the punch and the die. This can be a challenge when the operator is snapping the tool into place in the holder as it can be heavy, and the inclination is to hold it from underneath.

“Operators should put the press brake into tool-change-mode, which disables any contact of the foot pedal, which activates the ram,” said Ottens. He explained that workers should always be in tool-change mode when physically putting the tools in the machine. And for alignment, it’s important to put the machine in setup mode to bring the ram down safely.

“It is important that press brake operators are properly trained on how to set up and operate the press brake (including the safety/guarding system) and on correct material handling practices,” added Paul Sertis, customer solutions manager at Lazer Safe, Malaga, Western Australia.

Light Curtains

Shops have numerous safety device options to choose from. Light curtains are common on older machines, as the technology has been around for quite some time. Light curtains have a transmitter and receiver mounted on each side of the press brake bed that emit an array of synchronized, parallel infrared light beams in front of the work area.

“Generally, light curtains are set up so that the light barrier is active during the fast closing movement and the machine stops automatically when the tool opening is 6 mm,” explained Sertis. “This gap is considered too small for a hand or finger to enter the space between the punch and the material surface. From here, the operator can insert the material or workpiece, then press the foot pedal to complete the bend in slow speed.”

Operators need to know the safety features of every press brake to ensure they are running the machine safely. Photo courtesy of Lazer Safe

If an operator or object break enters the beam field before the ram reaches the mute point, the machine stops and will not continue until the obstruction is removed. Two types of light curtains are available, programmable and non-programmable.

“If you have what’s called a non-programmable light curtain, it doesn’t have the capability to set the type of part and cancel out some beams on the light curtain that interfere,” explained Ottens. “This means that the operator can’t physically run parts. It tries to make the ram come down to mute point, and then the operator basically inserts the part, which is not always possible.”

What usually ends up happening is the operator turns off the light curtain altogether, which leaves him unguarded and unsafe. A programmable light curtain allows for a part, say with a flange, to be inputted into the device, which cancels out the beams that would be obstructed by the part, allowing the ram to fully reach the mute point without stopping.

“Let’s say you have a 3-inch-tall flange on the part and the operator cancels out 3 inches of light beams; that’s enough space for an operator to slip his hand in, right?” said Ottens.

Another challenge with the light curtain is bending small parts. Mashinter explained that bending small parts often requires the operator to stand in front of the press brake and hold the part while it is being bent. With a light curtain, this is impossible.

Point-of-Contact Guarding

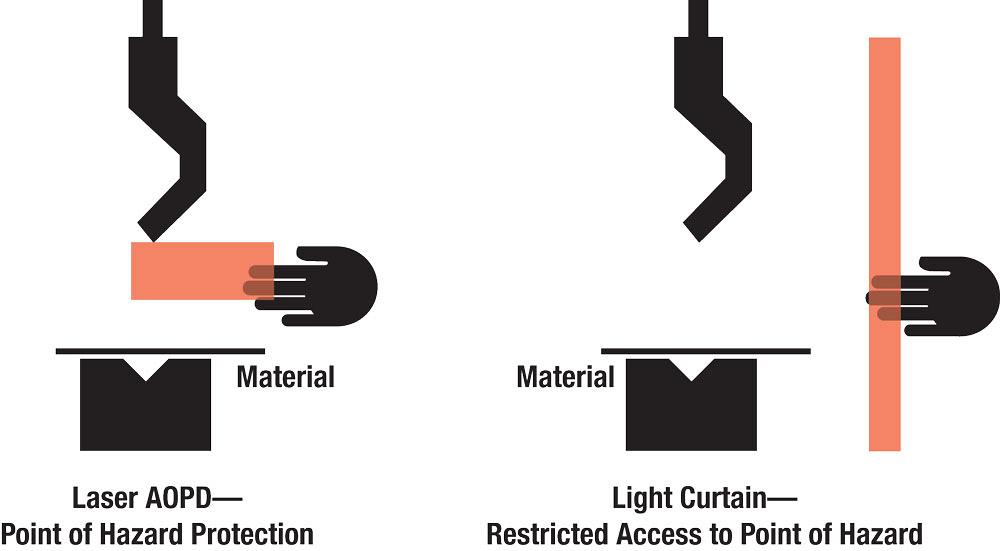

One of the newer safeguarding technologies to emerge is a laser active opto-electronic protective device (AOPD). This device is positioned under-neath or around the punch and a receiver transmits a laser light along the length of the press brake. Laser AOPD is designed to detect an object at the point of operation rather than just the space in front of the brake, like a light curtain does (see Figure 1).

“This device enables operators to stand closer to the machine and handle the material [especially smaller pieces] while the machine operates at high speed,” said Sertis. “Since laser guarding systems give the operator closer access to the point of operation, the safety requirements for these systems are more stringent because if there is any failure of the machine to stop, then the operator would be at risk of injury.”

Most newer press brakes have the capability to stop quickly because safety circuitry is built right in. If a finger is detected by the laser beam, it can stop the ram in a matter of microseconds.Another advancement in AOPD is the option for dual laser beams. Ottens explained that one laser can scan ahead of the other, which helps improve the performance of the machine.

“The first units that came out required you to slow the ram down way ahead of the mute point, so it would affect production quite a bit,” he said. “However, by using a dual laser system, or even now like an array of lasers, you get a much faster response time.”

The experts noted that AOPDs can be used in conjunction with light curtains, allowing for more flexibility. For example, light curtains are ideal for bending operations using multiheight tooling, so the operator can simply switch from laser protection to light curtain protection.

Figure 1—The main difference between a laser AOPD (left) and a light curtain system (right) is that laser AOPD protects the point of hazard, whereas a light curtain system restricts operator access to the point of hazard. Image courtesy of Lazer Safe.

“I’d say approximately 95 per cent of new brakes have some kind of coordinated point-of-contact guarding device,” said Ottens. “These devices were developed to provide guarding to the most safety-critical areas. It’s really been a great thing.”

Safety Standards

In Canada, CSA Z142-10 outlines the safety features and devices required to meet compliance standards related to press brakes. The previous standard was developed in 2002, so the new, updated standard needed to account for advancement in safety devices, particularly AOPDs, as well as standardize practices and provide consistency with EN 12622 (Europe) and ANSI B11 (U.S.).

According to Sertis, the new standards define three critical elements: optical detection area, automatic overrun monitoring, and safe speed.

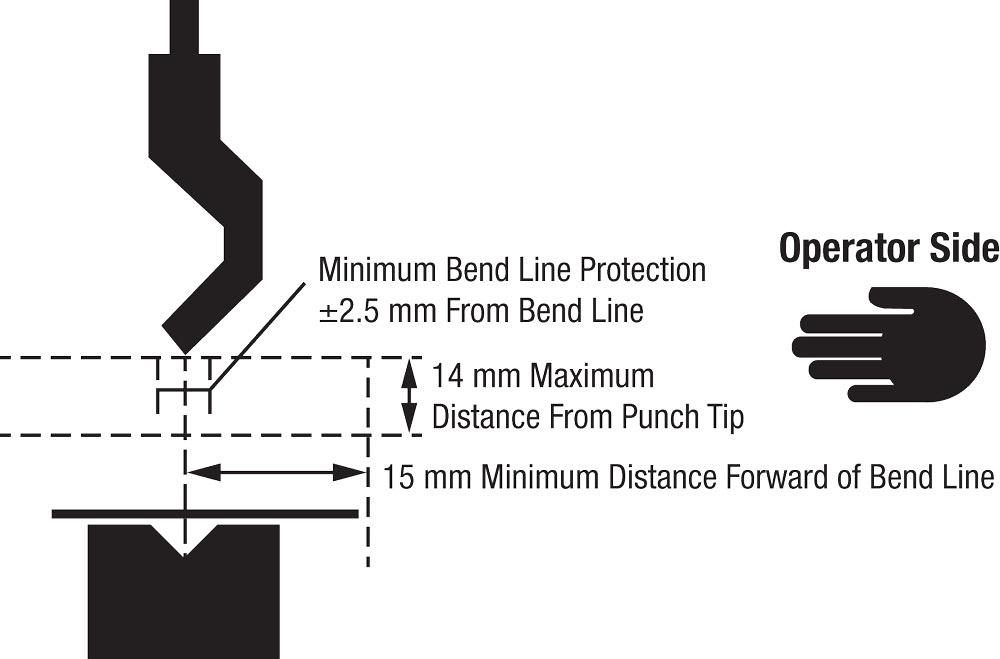

First, for optical detection area, the AOPDs must provide adequate coverage both below and for-ward of the punch die (the point that contacts the material first), he explained. The protective zone must extend across the entire length of the punch. The zone should extend forward of the bending line by at least 15 mm, and vertical detection must be a maximum distance of 14 mm from the punch tip to prevent an operator’s finger being inserted (and undetected) between the punch and the detection zone (see Figure 2).

Second, the machine must include automatic overrun monitoring. This is especially important because laser AOPDs are situated so close to the point of contact that ensuring no failure occurs is essential.

“This is required to automatically measure and monitor the distance that the machine takes to stop,” said Sertis. “This is critical because if the protective zone detects the operator’s hands or fingers, then the machine must be able to stop before it contacts the obstruction.”

Last, Sertis pointed out the safe speed is also defined in the standards, which is a speed no greater than 10 mm per second. The safe speed limit affords the operator enough time to react when operating the machine.

“During operation of the machine, there are situations where the protective zone must be deactivated (muted), for example, just before the punch contacts the material through to the completion of the bend,” he explained. “The protection can also be deactivated when the tool opening is greater than 6 mm (which creates a gap where a finger or hand could enter the space between the tools) so long as the speed is reduced to safe speed.”

“CSA Z142-10 is extremely thorough,” said Mashinter. “The maximum safe speed is clearly [defined]. And in Ontario, it’s a requirement to pass the Pre-Start Health & Safety Review (PSR). Every new press brake must be in compliance.”

Rules of Thumb

Beyond devices and standards there are some common best practices for safe bending operations. The experts agreed that it is essential for any operator to know his surroundings. It’s not just the point-of-contact area that can be cause for concern. Even with the latest safety devices, the workpiece still has the potential to cause harm. Mashinter gave the example of bending a large workpiece, which has the potential to snap up quickly as it bends and hit the operator or surrounding people in the chin or face. It’s not as common, but the potential is there.

Figure 2—This illustration shows AOPD detection capability minimum requirements. Image courtesy of Lazer Safe.

“If someone is around the back of one of our machines, we’ve included a safety curtain or a safety interlock because you wouldn’t want someone going around the back and getting caught by a part,” he added.

It’s important also to ensure that the machine has the correct tooling for the program running. If an operator loads the incorrect tool on the machine, which the machine doesn’t know, it could cause serious injury both to the operator and to the machine. It’s important to have the tools within the tonnage capacity. And although safety mechanisms are built into machines that monitor tonnage, a good operator will know if he can bend a particular thickness of material with any given tool.

“It really comes down to the operator being aware of the surroundings and his own knowledge and training to do it correctly,” said Ottens.

Associate Editor Lindsay Luminoso can be reached at lluminoso@canadianfabweld.com.

Amada America Inc., www.amada.com

Empire Machinery & Tools Ltd., www.empire-machinery.com

Lazer Safe, www.lazersafe.com

About the Author

Lindsay Luminoso

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

Lindsay Luminoso, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. She worked as an associate editor/web editor, at Canadian Metalworking from 2014-2016 and was most recently an associate editor at Design Engineering.

Luminoso has a bachelor of arts from Carleton University, a bachelor of education from Ottawa University, and a graduate certificate in book, magazine, and digital publishing from Centennial College.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Aluminum MIG welding wire upgraded with a proprietary and patented surface treatment technology

CWB Group launches full-cycle assessment and training program

Achieving success with mechanized plasma cutting

Hypertherm Associates partners with Rapyuta Robotics

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI