- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Streetcar sculpture re-creates historic tragedy

The commemoration of the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 involved a broad group of the city's fabricators and union talents

- By Treena Hein

- September 24, 2019

- Article

- Fabricating

The new sculpture at Portage and Main, shown in the process of installation here, honours the memory of the events of Bloody Saturday during the General Strike of 1919. Sculpture image courtesy of DMS.

Five years in the making and involving many fabrication techniques and four metalworking shops, a stunning commemoration of the Winnipeg General Strike was unveiled on June 21, 100 years to the day after Bloody Saturday.

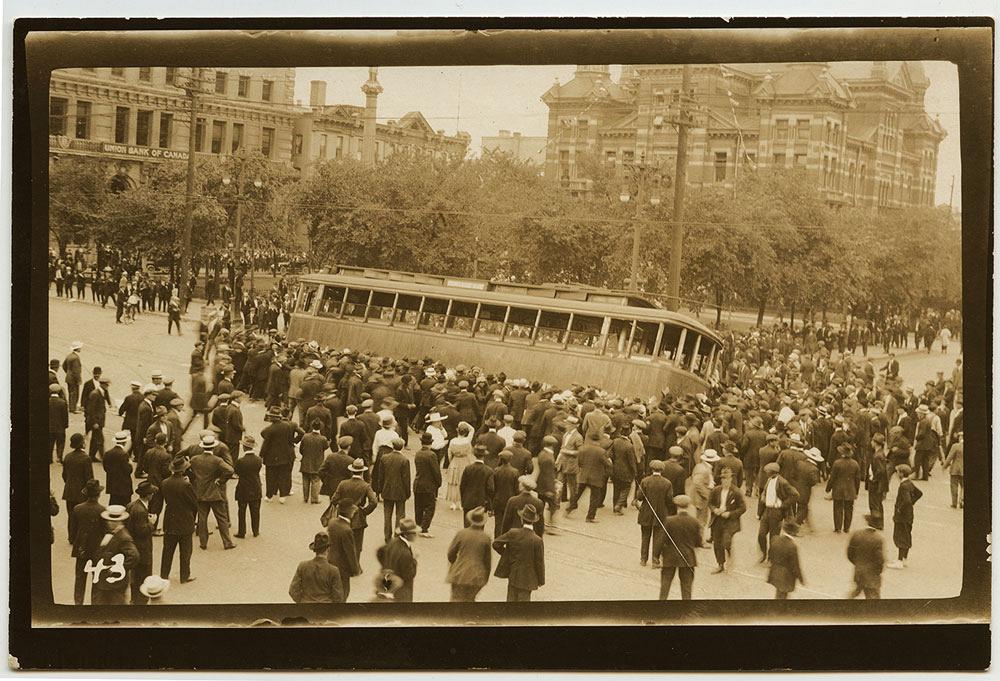

If that reference doesn’t ring any bells, let’s brush up on what is a piece of tragic Canadian history. About a month after what became known as the General Strike began, several of the strike leaders were arrested, and on June 21, 1919, an already tense situation boiled over. Masses of strikers and their supporters converged on city hall, downtown at the intersection of Portage and Main. A streetcar happened to approach, and in it, the protesters found a focus for their anger. Streetcar operators were part of the strike, and the cars were still running through the use of replacement workers.

People rocked the streetcar and even pushed it off its tracks in an attempt to tip it over. After some time they gave up on that and began smashing its windows. A few protesters went inside, slashed the seats, and set the car on fire. Meanwhile, the North West Mounted Police and hundreds of “special” constables hired by the city moved in to re-establish order. Many people were beaten, and two people lost their lives by way of police gunfire. Images of the streetcar billowing smoke became iconic.

Five years ago, as the 100th anniversary of this infamous event approached, a filmmaker named Noam Gonick approached sculptor Bernie Miller to help conceive of a way to commemorate the event. A sculpture of the streetcar, the lasting symbol of the strike, seemed logical.

After it was commissioned by the Winnipeg Arts Council, Gonick and Miller looked at photos from Bloody Saturday and examined a restored streetcar at the Winnipeg Railway Museum. Unfortunately, just when they had finished a design during fall 2017, Miller passed away. “But by that time, the momentum was there,” said Gonick. “There was cash investment from Manitoba’s labour unions first and foremost. The federal government also provided matching funds.”

In 2015 Gonick and Miller approached Cesare Sacco, who was general manager at Parr Metal Fabricators at the time and is now officially retired but still active at the firm. They discussed materials and prices, and Parr performed the stainless steel rolling and bending. “There were quite a few compounding angles, so it took more time, and it was a challenge sometimes to make the drawings work,” Sacco said.

As the planning progressed, it became clear that another shop would need to be involved. In short, everyone involved felt that a sculpture commemorating a historic union worker event should involve a union shop. That shop was DMS Industrial Constructors in nearby Transcona (Iron Workers Local 728), which ended up doing most of the fabrication.

“It was our first job like that,” noted Stan Hrncic, the sculpture project manager and structural manager at DMS for the last 14 years (Stan’s brother Kris was also heavily involved). “We do jobs of all kinds but have never done a sculpture. We started up in 2003 as an industrial piping outfit, then expanded to making platforms. In 2014 we expanded again into a full industrial contracting operation, with electrical and engineering divisions, and so on.”

The build, in stages, took about 10 months. While the stainless steel framework was fairly straightforward, everything had to be adjusted for the angle to make the car appear as if it were tipping over.

The sculpture then sat for about three months while the plans for how to achieve the final look were finalized. “The finish was first planned to be silicon bronze, and the galvanic reactions between the two were going to be fine, but the price of bronze cladding was about $200,000,” Hrncic explained. “So we ended up going with weathered steel. The galvanic reaction with stainless steel and steel meant we had to apply a rubber membrane, similar to a truck liner but softer. It came out to only about $23,000 for the entire finish.”

The cladding was challenging, however, because there were many angles to deal with as they worked off drawings and with the form team at Parr. “The drawing would have an error, and so we had to weld in a piece or two here and there,” Hrncic recalled. “The four corners on the top of the car, they’re rounded, and it took a bit of time to figure out how best to fabricate them. We ended up doing an online search and found a company in B.C. that spins steel, AMS Industries in Vancouver. We sent them the four pieces of corner cladding, and they spun them and then we cut them into the right shape.”

Another challenge – at least in terms of time and muscle – was drilling all the holes in the stainless steel frame to anchor the cladding, 1,100 holes, to be exact. “We were able to plasma-cut some of them, but we couldn’t set up a drill press for much of it, so the guys had to set up vises and use steel drill bits and drill by hand,” explained Hrncic. “Too fast you burn out, too slow you burn out the bit, so the guys learned the rhythm. But it was pretty time-consuming.”

Another local shop called Dynamic Machine Corp. did the grooving on the outside panels, and at the end, Central Sandblasting & Powder Coating was called in. “We sandblasted it for two reasons,” Hrncic said. “Initially we weren’t going to, but if we didn’t, it wouldn’t have turned that bronze colour for about a year at least. We also had a lot of little markups to remove. We didn’t want to use acid washing and we didn’t want grind marks, and we were also running out of time, so we got it blasted. It was a good way to go. It made it all uniform and removed all the imperfections and marks.” Hrncic added that not long after the sculpture was installed, it rained, and within about 15 minutes, a beautiful bronze colour shone through.

Among others, Gonick was relieved to see the project finished as the 100th anniversary approached. “We got it done only a few days before deadline,” he said. “Everyone worked very hard. I really liked the process of working with the ironworkers. They are very detail-oriented, and in making something that doesn’t exist anymore, they were definitely up to the task of using older fabrication techniques to make sure it looked authentic. I was very impressed with that. When you drive by it, you really feel like you’ve gone back in time.”

For Hrncic, being involved means a lot to him personally and he believes that feeling goes for everyone else at DMS who worked on the sculpture. “I’m proud of it,” he said. “I’m not one to brag about a job, but it’s well done. I’ve been on a large number of projects, pretty fancy structural crane structures in many provinces, but this one is about being part of history. Being a union shop, we’re particularly proud to be a part of it.”

He said the sculpture should last 100 years, which is fitting.

Quick facts- Sculpture size: 9.75 m long (32 ft.), 2.4 m wide (8 ft.), and 3.7 m (12 ft.) at the tallest point

- Sculpture location: Portage and Main, downtown Winnipeg

- Angle of sculpture (so that it appears to be tipping over): 20 degrees

- Number of fabrication shops involved: 4

- Total number of workers on the project: Over 25 (12 at DMS, several at each of the other shops)

- Designers: Filmmaker Noam Gonick and the late sculptor Bernie Miller

- Years since streetcars ran in Winnipeg: 64 (1955)

- What they were replaced with: Trolleys and diesel buses

Treena Hein is an Ottawa-based freelance writer.

Historic image from Archives of Manitoba, A 0272 Exhibits and other records related to the Winnipeg General Strike trials, GR3081, R v. Ivens et al exhibit 998 (front), G 7494 file 3.

About the Author

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

CWB Group launches full-cycle assessment and training program

Achieving success with mechanized plasma cutting

3D laser tube cutting system available in 3, 4, or 5 kW

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

Welding system features four advanced MIG/MAG WeldModes

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI