Associate Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Don’t let interruptions slow you down

Choosing the right insert for interrupted turning helps ensure a smooth process

- By Lindsay Luminoso

- February 21, 2022

- Article

- Cutting Tools

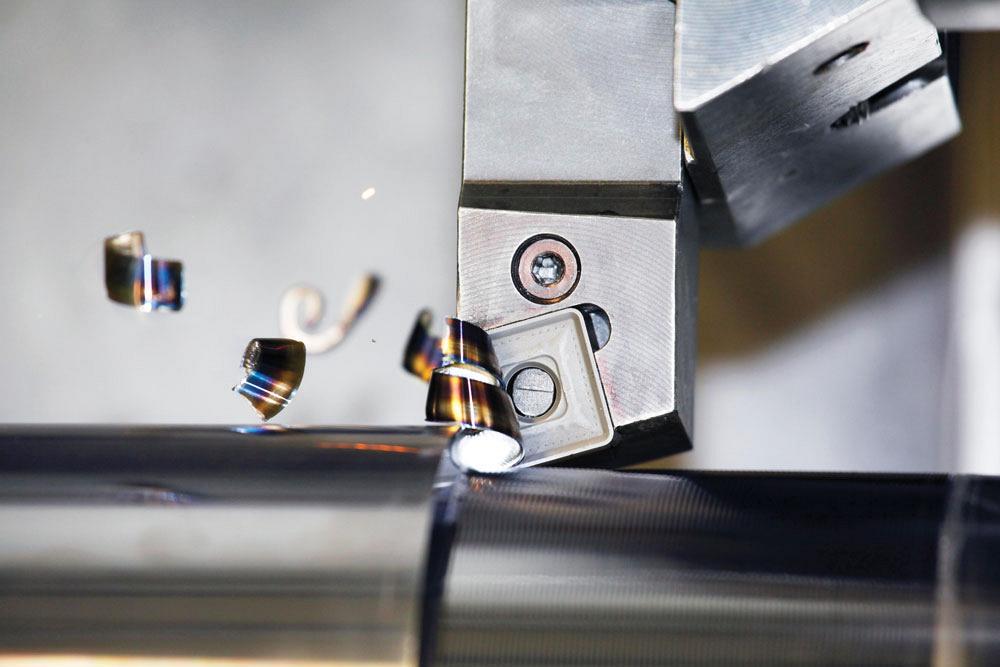

With interrupted cuts there is a greater risk for the cutting edge to break down prematurely or inconsistently, lowering part quality. It is important to choose the best cutting tool and process parameters during interrupted turning operations. Phuchit/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Interrupted cutting in turning is subjective. While some operators may look at a part with a keyway and a small depth of cut as a heavy interruption, another operator may classify heavy interruptions only as multiple interruptions with a larger depth of cut. The workpiece material, part configuration and features, and depth of cut will all come into play when determining how the interruption will affect the overall process.

Regardless of how a shop classifies interrupted cuts, interruptions can present themselves in a couple of different ways.

“Most commonly, an interruption is a break in the continuity of the material during the machining process,” said Matt Goss, applications engineer and project development, Greenleaf Corp., Saegertown, Pa. “This is where the insert engages and disengages with the workpiece, either once or a series of times. These interruptions can either be induced as part of the machining process, such as turning over bolt circles or holes, slots, or keyways, or they can be inherent to the workpiece, for example if it is out of round or has forging scale on the surface. Each of these cases presents a scenario where there's a break in continuous and uniform flow of material across the cutting tool.”

An interruption also can be experienced not in the physical sense of material discontinuity, but by an inconsistency in material hardness or having heterogeneity in the material makeup of the workpiece. Goss explained that heterogeneity in the material can occur because of precipitates or inclusions that form during the manufacturing process of the parent material. If these precipitates or inclusions are congregated in one area of the workpiece, they can also act as an interruption during the machining process.

The impacts of interrupted cuts will depend on the process itself, whether it’s a roughing or finishing application. For the most part, roughing applications tend to include interruptions from forged or cast workpieces that are irregular in material or non-concentric shapes.

“The benefit of dealing with interrupted cuts in the roughing stage is that the insert can be changed, from part to part, without an offset,” said Matthew Haid, application specialist, Dormer Pramet, Mississauga, Ont. “Dealing with interrupted cuts in finish-turning can be much more challenging. If the part has a tight finishing tolerance, operators typically need to adjust the tool wear offset on the CNC over the course of the insert’s life. When changing the insert, it's recommended not to start at zero or the regular offset, but rather do a first pass to confirm the tolerance dimension. Both interrupted roughing and finishing can be a challenge, but with roughing, there is always material left to be finished, whereas finishing tends to be more sensitive.”

Levels of interrupted cuts can vary anywhere from a light interruption, which might account for only 10 to 20 per cent of the overall process, to a heavy interruption which can be 60 to 75 per cent or more of the overall process. Regardless of how you define interrupted cutting, there are some points to consider when undertaking an interrupted operation.

Cutting Tool Specifications

Choosing the right insert for interrupted turning can make all the difference in success of the overall process. One of the big misconceptions is that operators can just use whatever insert is available. Sometimes this may work out, but often operators will struggle.

Grade. Cutting tool materials often are a balancing act between hardness and toughness.

For example, a hard grade of carbide will run faster and last longer but is more brittle, whereas a tough grade of carbide has impact resistance but runs slower and does not last as long.

A rigid setup is necessary for interrupted cuts to take the impact. A round insert is the strongest, followed by a square insert. Dormer Pramet

According to John Mitchell, general manager, Tungaloy Canada, Brantford, Ont., carbide cutting tools are made primarily of tungsten, a very hard, wear- resistant material that is bound together with cobalt. To produce a grade capable of handling interrupted cuts, traditionally cutting tool manufacturers simply used more cobalt. On the other hand, to make the insert more wear-resistant, capable of faster cutting speeds and longer tool life, manufacturers used grades that had less cobalt and more tungsten.

“Tungaloy developed a technology that was able to draw the cobalt to the outer edges of the insert, giving just the cutting edge a higher concentration of cobalt,” said Mitchell. “This allowed for the best of both worlds: a carbide grade with a high concentration of tungsten to allow for higher cutting speeds and longer tool life, while at the same time providing additional concentration of cobalt at the cutting edge to provide additional impact resistance.”

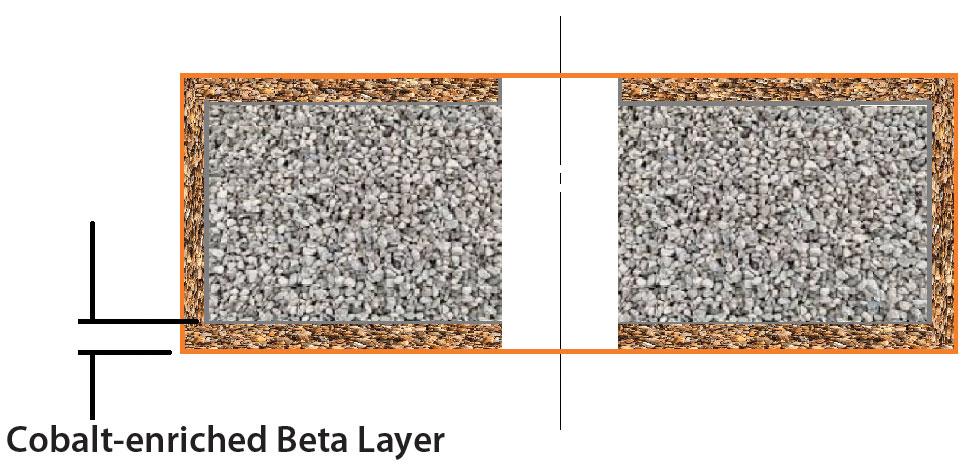

With carbide grades, having either a large grain size or cobalt-enriched layer as part of the substrate will make for a stronger insert. Larger carbide grains have more impact on strength compared to a fine-grade carbide.

“However, with ceramics, we would recommend opting for a silicon-carbide, whisker-reinforced ceramic insert or a silicon nitride-based ceramic over an alumina-based or white ceramic, as it will provide much more strength and reliability,” said Goss.

Choosing the right grade depends on the type and hardness of the material, as well as the level of interruption and the machining stage, whether roughing or finishing.

“For roughing applications, I would like to have a tougher grade with a larger T-land or a roughing chipbreaker with a nice edge prep to maintain the interruptions as well as hold that dimensional tolerance,” said Haid. “When finishing, go with something harder rather than something tougher to hold the tolerance and not wear out as fast.”

Coating. For interrupted turning, an insert with a physical vapour deposition (PVD) coating on the substrate will help extend tool life. PVD coatings are tougher than chemical vapour deposition (CVD) coatings.

“PVD coatings have a thin layer that really holds up better against the impacts of interruptions versus the CVD option,” said Haid.

Shape. The experts agree that while different shapes of inserts may work, a round insert is the best option, followed by a square insert.

“If you have the corresponding toolholders in your facility already, a round insert is the strongest,” said Haid. “With a round insert, a rigid setup is necessary to take the impacts of the interrupted cuts. A square insert would be the second strongest. For the most part, diamond-shaped inserts are not well suited, but some interruptions could require a specific insert to get in and perform the cut.”

When you are considering carbide grades, having either a large grain size or cobalt-enriched layer as part of the substrate will make for a stronger insert. Tungaloy

Geometry. Another consideration for interrupted cutting is the geometry of the insert. Choosing an insert that has a small nose angle and long, narrow cutting edge does not offer the rigidity needed in most interrupted cutting applications.

“Basically, you want to look for the strongest insert possible,” said Paul Lobsinger, sales and service engineer Canada, Greenleaf Corp. “It helps to have a tough negative insert to accept the interruptions and pounding.”

The experts noted that some operators tend to favour a positive geometry as they think it will help take the impact, but that is just not the case. A negative geometry is going to provide a much better cut in interrupted turning.

“Although positive inserts are generally not recommended for interrupted cuts, sometimes they are unavoidable,” said Mitchell. “In situations such as these, it is highly recommended to use a double-sided positive insert. Traditional positive inserts sit in a pocket and the only thing preventing them from moving is a small screw. But [some inserts] utilize a dovetail pocket, ensuring no movement even in interrupted applications, while still providing a positive cutting action.”

Optimal strength is going to be realized by using a round geometry and a negative-style insert. Mitchell also noted that it’s important to pay attention to the chipbreaker selection. Some chipbreakers are designed for heavy interruptions, but others are designed to be free cutting and as sharp as possible, making them fragile and prone to chipping in an interrupted application.

The right chipformer or edge prep for interrupted turning will depend on the workpiece material.

“For interrupted-style cuts on hardened material, it’s best to choose heavier edge preparations,” said Goss. “With ceramic, having a large single or compound chamfer/land, or with carbide, having a heavier-duty chip form, will ensure the insert is able to handle the abusive nature of the cut and redirect those forces appropriately to allow for maximum tool life.”

For interrupted cuts in softer or more ductile materials, having an edge prep with a larger or wider land is a good option. With ceramic, the insert does not need to be as negative as it would for a harder material; with carbide, a medium-duty chip form will provide additional shear, which is beneficial in most cases.

“There needs to be a balance,” said Goss. “You don't want to have too much negativity or a large land on some of those soft, ductile materials, which could lead to excessive cutting force. But it also needs to be heavy enough to provide adequate performance and tool life.”

Best Practices

Some of the impacts of interrupted cuts on the turning process can, depending on the severity of the interruption, lead to accelerated tool wear. This increased tool wear can lead to more tool changes during the process, which ultimately leads to an increase in part cycle times and an overall increase in labour and tooling costs for the job. Here are some factors to consider to help limit tool wear.

Speeds and Feeds. The experts agree that one of the biggest mistakes an operator can make during interrupted turning is to reduce speed.

“When it comes to ceramics, you want to avoid this temptation,” said Lobsinger. “It’s the first thing an operator will do when they start thinking something is going wrong, but you definitely don’t want to do that. The amount of increase in the recommended speed in severely interrupted cuts can usually be calculated. The operator can calculate the circumference of the part, then subtract the total sum of the interruptions. This will give a smaller diameter value, which increases the SFM. Essentially, when increasing cutting speed, you're reducing the time the insert spends out of the cut, thus reducing how much time the insert has to cool, ultimately reducing thermal stress and the growth of the cracks.”

Lobsinger explained that the smaller diameter value basically returns the operator back to the original recommended surface speed he is trying to achieve.

“A simple example of this would be 50 per cent of the material taken away by voids or interruptions at the surface,” he said. “Fifty per cent of the surface remains in contact with the tool compared to an interrupted part. So, in this case, double the SFM to compensate for that.”

Haid added that it’s always better to start on the low end of the feed rate to provide a bit of wiggle room, rather than running a little bit slow. Running slow can put more impact on the insert.

Coolant. The issue of thermal stress leads some operators to believe that running the machine with coolant is the best option.

“However, coolant should almost always be shut off, unless machining an extremely gummy material,” said Mitchell. “When coolant is applied to an insert machining an interrupted cut, the insert undergoes extreme heat, then no heat when encountering the interruption. The hot insert is then suddenly submerged in coolant, which causes thermal cracking, shortening the tool life and potentially causing catastrophic failure.”

Associate Editor Lindsay Luminoso can be reached at lluminoso@canadianmetalworking.com.

Dormer Pramet, www.dormerpramet.com

Greenleaf Corp., greenleafcorporation.com

Tungaloy, www.tungaloy.com

About the Author

Lindsay Luminoso

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

Lindsay Luminoso, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. She worked as an associate editor/web editor, at Canadian Metalworking from 2014-2016 and was most recently an associate editor at Design Engineering.

Luminoso has a bachelor of arts from Carleton University, a bachelor of education from Ottawa University, and a graduate certificate in book, magazine, and digital publishing from Centennial College.

Related Companies

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Automating additive manufacturing

CTMA launches another round of Career-Ready program

Collet chuck provides accuracy in small diameter cutting

Sandvik Coromant hosts workforce development event empowering young women in manufacturing

GF Machining Solutions names managing director and head of market region North and Central Americas

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI