Technical Advisor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

How to choose a round tool

Indexable, solid-carbide, and exchangeable-head round tools all have their place in part processing

- By Andrei Petrilin

- October 11, 2019

- Article

- Cutting Tools

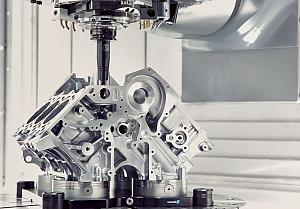

Iscar’s T890 indexable insert has a complex shape made possible by the use of powder metallurgy technology.

Indexable or solid? Which rotating tool design concept is better? As in many subjects of tooling technology, there is no absolute answer to this question. However, a definite answer emerges when the advantages and disadvantages of both design concepts are considered on the basis of specific conditions.

A look at indexable tools

An assembled tool carrying removable indexable inserts, a concept that has been common in industry since the 1960s, requires cutting capabilities from only one of its components: the insert. The cutter body acts as a holder for inserts of a specific shape produced from different hard-to-machine tool materials (such as cemented carbide grades, cubic boron nitride, and cermet), while the body itself typically is made from steel.

The inserts can differ in their chip forming surface to generate the necessary cutting geometry. Clamping the insert, which has the geometry and material suitable for cutting the workpiece, in the body results in an optimal cutting tool.

Inserts have several cutting edges. If one edge is worn, it is simply replaced by indexing the insert by means of rotation or reversing. The indexable principle ensures cost-beneficial utilization of the tool material.

Inserts are formed by powder metallurgy technology to produce the unique shape of the chipforming surfaces; obtaining this shape by other technology methods is extremely difficult or even impossible. Powder metallurgy creates an exceptionally strong cutting edge capable of standing up to heavy loading.

At the same time, an indexable tool has disadvantages.

First, accuracy is lower compared to a solid cutter. Second, the tool diameter cannot be relatively small (less than 0.315 to 0.375 in.). Reducing the diameter leads to diminishing the size of all assembly components, including the insert and its clamping elements (usually a screw), which have a natural dimensional barrier.

In addition, the insert’s cutting edge is strong but not as sharp as that of a solid tool. For machining soft materials like copper, commercially pure titanium, and aluminum, which require a sharp edge, additional edge grinding needs to be performed.

Moving to solid tools

The main advantage of a ground solid tool is its high precision. However, a solid tool cannot be indexed, but it can be reground.

Like an indexable cutter, a solid tool also has dimensional limitations that relate to the tool cost. As opposed to the indexable concept, the solid tool cannot be relatively large in diameter. Usually the diameter of a solid tool does not exceed 1 in.

This type of tool demands significantly more tool material, and it takes more time to manufacture such a tool by grinding. These constraints lead to a higher tool cost. By contrast to the indexable tool, the cutting edge of the solid tool is sharper, but it is not as strong.

How to choose

The machined surface dimensions of the workpiece typically dictate the tool concept that should be used. For example, for drilling a 0.12-in.-dia. hole a solid drill should be used.

Aside from this dimensional aspect, the following principles characterize correct tool selection:

- Heavy cutting. For heavy cuts (usually roughing or semi-roughing) that require significant cutting force and power consumption, an indexable tool is the preferred choice.

- Light cutting. If an operation requires light cuts and demands high accuracy and surface finish, then a solid tool is the best choice.

This logical -- and traditional – concept has undergone a dramatic change over the past few years. The search for new ways to improve productivity, combined with advances in machine tool engineering, has engendered efficient cutting strategies and appropriate machines.

A significant number of modern machines have less power but far higher speed drives and advanced CNCs for high-speed machining, performed by a small-diameter tool moving at an optimal trajectory for constant tool loading.

This step, together with progress in regrinding and recoating technologies, means that solid tools now can be used in rough machining. In addition, advances in tool materials have increased the hardness level at which workpieces can be worked. Today, for example, solid-carbide end mills operated in a high-speed milling operation can cut hardened steel up to 65 HRC.

Combining the best of both

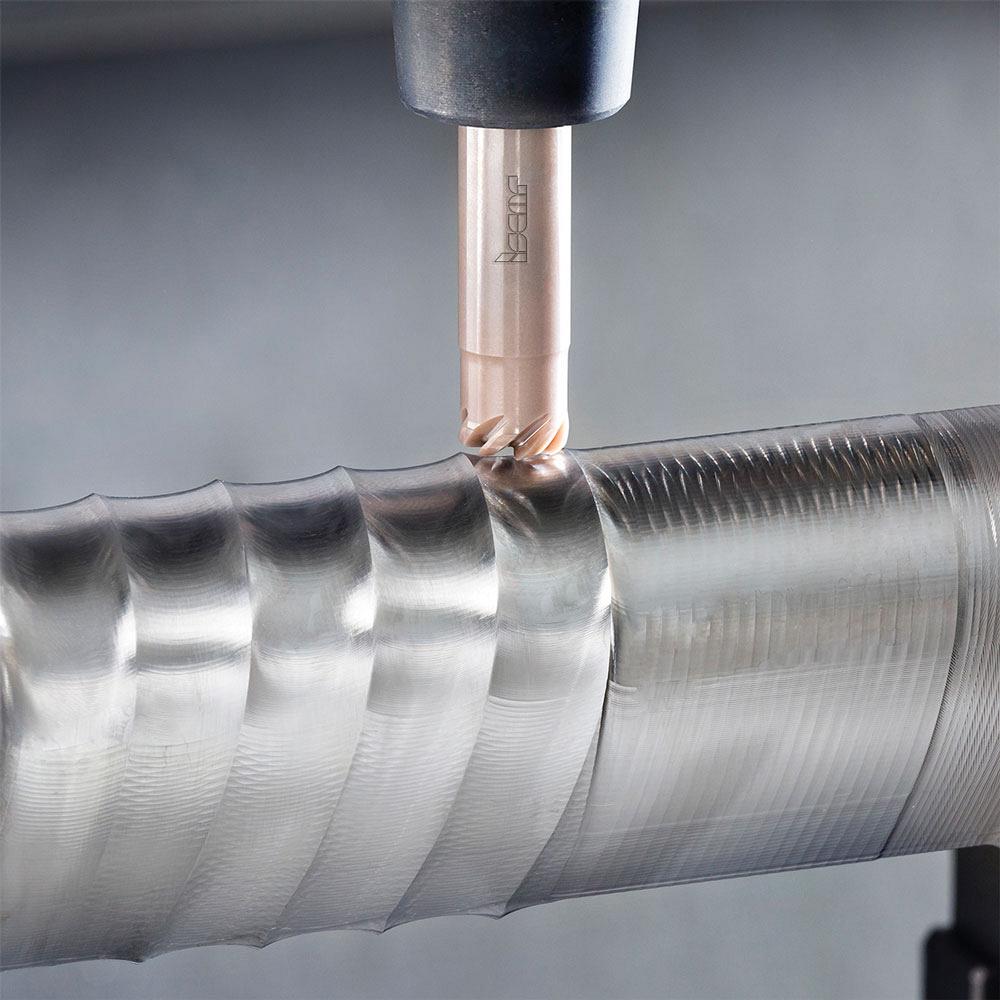

Tool manufacturers recognized the advantages of combining both solid and indexable concepts into a single design to meet today’s machining challenges. An example is a tool with exchangeable cutting heads made from solid carbide.

An exchangeable cutting head can be mounted in different bodies, and a body can carry different heads. This “indexable solid” principle enables many possible tool configurations.

So, which concept is better?

The industry requires both types of cutting tool, depending on technology processes. The ratio of indexable tools to solid and “indexable solid” tools in today’s market is estimated at 1-to-1, which indicates how cutting tool development is progressing in both directions.

Drills with exchangeable carbide heads combine the design concepts of both indexable and solid tools.

But technology advances and improvements in processing will make tool requirements, whether solid or indexable, more and more demanding.

Andrei Petrilin is technical manager of indexable milling for Iscar Tools, 2100 Bristol Circle, Oakville, Ont. L6H 5R3, 905-829-9000, www.iscar.ca.

About the Author

Andrei Petrilin

2100 Bristol Circle

Oakville, L6H 5R3 Canada

905-829-9000

Related Companies

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI