- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Collaboration Is Key to Creating a Skilled Workforce

Industry, government, educators, and media collaborate to create tomorrow’s skilled workforce

- By Sue Roberts

- July 11, 2013

- Article

- Management

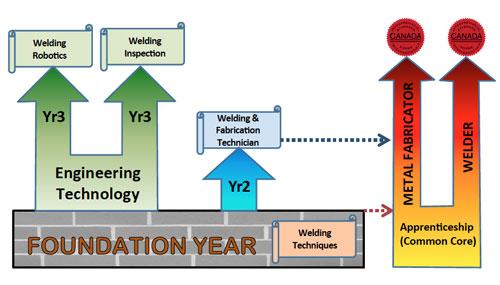

Established pathways leading from certificate programs to apprenticeships to engineering and perhaps MBAs can help manufacturing students define their goals and advance their careers. Image provided by Conestoga College.

There seems to be no question. Now is the time to bring manufacturing back to Canadian shores. With costs of living and salaries edging up in countries traditionally providing low-cost labor, climbing transportation expenses, and a growing awareness of hidden costs such as a need to maintain inventory, production delays, and currency exchange, the advantages of offshore manufacturing are dwindling.

Add the need for more jobs at home. Reindustrialization opens manufacturing jobs and, in turn, creates support jobs. According to Deloitte & Touche, for every 10 jobs created in manufacturing, six more are spawned in nonmanufacturing sectors.

Increased production demands trained machinists, metalworkers, millwrights, sheet metal workers, and welders, as well as engineers, to support the trades, jobs that industry members recognize as good career paths but that don’t appear as blips on the radar of most young people. Then there is the challenge of ensuring that students who do find their way into manufacturing programs learn the skills needed to be effective when they enter the real world.

The question is, who will fill those positions? The answer is multi-faceted. It requires collaboration among members of industry, federal and provincial governments, media, and educational institutions.

Four industry members turned educators look at manufacturing education.

We’re slowly convincing the population and leaders of the nation that we need to reinvigorate manufacturing. Manufacturing was a dirty word to a lot of people; we were going to rely on our natural resources and be a service economy. But it is critical that we add value to the raw materials and keep as much as possible of those value-adding processes in this country.

We’re trying to improve communications with the secondary school system, to reintroduce the benefits of working with tools and the satisfaction it brings, and to increase the focus on the STEM subjects—science, technology, engineering, and math—so people are prepared for the manufacturing jobs of the future.

When a school system sees students who are weak in mathematics, they too often direct them toward the trades when the opposite should happen. Tradespeople may do more practical math on a day-to-day basis than any other profession—estimating and measuring material for layouts, calculating weights for a crane pick, and so on. That needs to be understood by the entire education system.

We are working with other institutions to establish well-defined pathways to guide students through trades education. Colleges and degree programs need integrated programs so a student can start as an apprentice, potentially go on to engineering technology, progress to a degree program if the desire and aptitude are there, and perhaps on to an MBA. Right now those pathways are pretty murky.

Every college in Ontario has a program advisory committee comprised of active industry people, possibly a representative from the apprenticeship board, and representatives from the high schools and other educational institutions. These committees keep our feet on the ground.

Jim Galloway, BASc, CETProfessorCoordinator of Welding ProgramsConestoga College-Cambridge CampusCambridge, Ont.

The government programs are there to move manufacturing education forward. Educational institutions are ready, willing, and able to train, but industry also needs to participate. Young people need to be encouraged to enter the trades programs and know that they are not dead-end careers. Manufacturers need to host interns, train apprentices, and participate in guiding the training programs at their local colleges.

A downfall of the manufacturing industry in North America has been that the people who run the companies don’t know how to build the product. People come out of university with an MBA, for example, and make key business decisions when they don’t know what’s involved in the product’s production.

The Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) Shell Manufacturing Centre is like a sandbox for industry. Industry members come to the Centre for leadership training, staff development, and technology adoption. We have assembly and welding robots, laser cutting machines, an environmental test center, and RFID technology that includes passive and active tags (microchips) to track product and help integrate automatic reordering systems. The Centre is reserved four days a week for industry use and the remaining three days per week is open for NAIT programs, student projects, and applied research.

We assist organizations with change. As soon as a company says it is going to bring in robots or automation, the reaction is an undercurrent among the staff who believe their jobs are in danger. We help companies create a comfort level and communicate that the automation is to help the company become more competitive—move product faster, produce more, gain market share—not reduce workforce. The company needs to understand that their employees are the strong foundation of the organization. They add value to the products that end up with the customers.

We create a strong link between the involvement, commitment, and the impact of organizational culture. We help students and industry participants learn how to create a very positive, constructive, and productive company culture.

The Centre is 100 percent self-funded. We received original equipment funding from industry and government when we opened, but receive zero operating funds. Money accrued though our services is used for operations and to keep the equipment up-to-date (evergreen).

Programs for our corporate clients are suitably customized to meet their needs. At the time of completion, approximately 70 percent of the people in these programs tell us that their actual roles at work changed while they were attending NAIT, not because they were looking for change, but because the people around them notice a difference in their behavior and ability to contribute to organizational goals.

NAIT Shell Manufacturing Centre looks at the larger picture, not just what we can do or what we can train people to do. Canada is a great place to live and has one of the best standards of living, but we need to increase productivity to maintain that standard. When manufacturers focus on that larger picture as they make their organization more successful, they contribute to national growth and stability.

Manufacturing education has evolved so it is no longer hard-core nuts and bolts. Classes are so multi-disciplinary that it takes someone with a broad range of skills to deal with the topics and development issues. However, manufacturing doesn’t sell with the youth. They don’t appreciate how demanding, how technically advanced it is. We try to attract students by showing elements of manufacturing’s advanced automation—but we have to get the students in the door first.

In the last 10 years, it’s not so much the demise of manufacturing engineering programs as the growth and expansion of mechanical engineering programs. Students tend to be attracted to sexy, new programs like biomechanics, mechatronics, and nanoengineering. So we develop these programs. Everyone graduates as an engineer, so they are qualified for manufacturing jobs as well as the jobs in a specialty area.

During the course of their education we expose them to elements of real manufacturing. Speakers at a recent seminar were upbeat about the advantages of new software and rapid prototyping. I turn it around and say they are exciting from the standpoint of attracting students.

We’re fairly good at keeping up with new technologies. The problem is that when we introduce something new, we have to get rid of something old while still providing education in the basics. We constantly juggle the education mix for the four-year program. The problem is keeping pace on a limited budget.

Credit goes to the provincial and federal governments for introducing industrial internship programs at the graduate level. It’s a great idea to get advanced students working in industry as well as making industry aware of what the students can do. Getting a grad student in a company for a summer is not a big investment, about $10,000, but the advantages for both parties are extremely worthwhile. There is no lack of industrial partners; the problem is finding enough domestic students.

We’re also working to get transferability going across the province and across Canada. The government wants to see two years at any college in Ontario transferring to any university in Ontario. It makes sense. If you have partnerships between the colleges and universities, you can produce greater numbers of more capable people with the same money.

We recently went through a mapping process where we asked what was needed from people coming out of an entry-level, one-year certificate program. Members from a cross section of industry talked about industrywide requirements. After we completed the process, we saw that what we had and where we needed to go weren’t very far apart. It was good validation for what we are doing, but some course adjustments were made. We added a little more focus on inspection, geometric tolerancing, design, and CNC training.

We try to train our students on as relevant equipment as possible. Industry partners like Sandvik Coromant have given generous donations for both equipment and student scholarships.

We promote manufacturing education in the high schools, through open houses, and such to introduce younger people to our programs. We set up areas called Try-A-Trade® where students, with a little help, actually try a trade. Television documentaries paired with websites like “How It’s Made” and “American Chopper”; competitions like Skills Canada where young people can see what a machinist, welder, or electrician does; and Skills Work® summer camps that give kids hands-on experience are helping create interest in manufacturing.

Our student numbers in Alberta had dropped drastically, but now they are creeping back up. Next year we are scheduled to have 330 apprentices come through the machinist trade. It’s getting better and we expect it to continue to grow.

In a perfect world all companies would be involved in apprenticeship programs. I was fortunate during my apprenticeship because the company moved me around to do different tasks. Between the classes and the work experience, I received a well-rounded education.

Industry needs can change very quickly, and we need to keep in touch with industry to keep up. Need is the mother of invention.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

- Industry Events

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI

17th annual Joint Open House

- May 8 - 9, 2024

- Oakville and Mississauga, ON Canada

MME Saskatoon

- May 28, 2024

- Saskatoon, SK Canada

CME's Health & Safety Symposium for Manufacturers

- May 29, 2024

- Mississauga, ON Canada