Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

The Right Rough

Optimized roughing increases Q rate, decreases cycle time

- By Joe Thompson

- August 22, 2017

- Article

- Cutting Tools

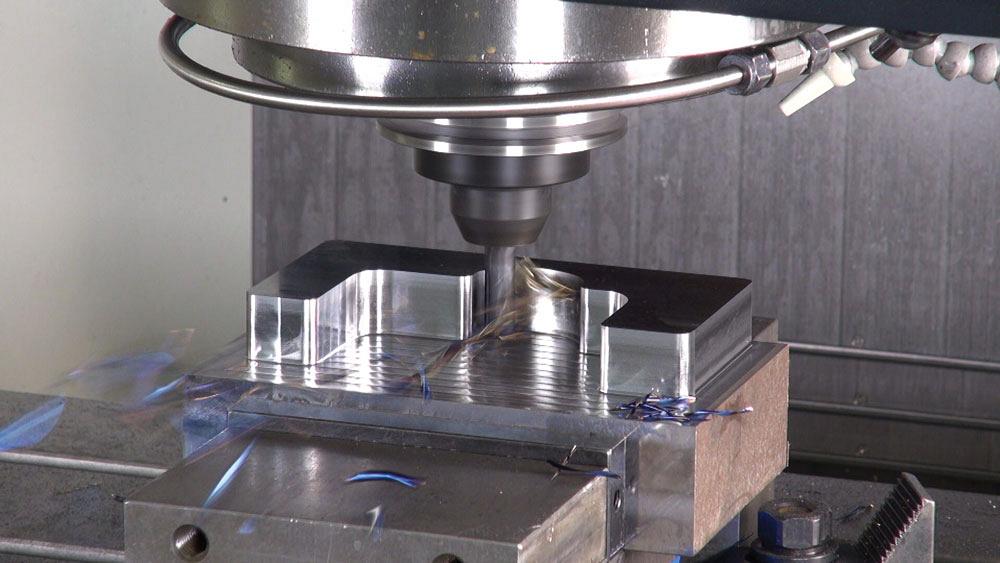

The best use of the optimized roughing technique is in situations that can use the full flute length of the tool, such as roughing long, straight walls. Photo courtesy of Seco Tools.

Creating metal parts quickly, efficiently, and on spec is the requirement of every shop.

During the roughing phase, the vast majority of material is removed from the part, typically leaving only what is required for the finishing phase.

“Today’s CAM software can be programmed to create an optimized roughing stage that uses a large DOC and light radial engagement to maximize metal removal rates. It’s a type of milling operation that is very well suited to pocketing and side profiling,” said Jay Ball, product manager for solid-carbide end mills – NAFTA at Seco Tools.

For the optimized roughing operation to be successful, a constant radial DOC must be maintained. This radial DOC also depends on the material being cut. For example, superalloys can have a radial DOC that is 5 to 7 per cent of the tool diameter, while tool steel under 50 HRC can use 7 to 10 per cent of the tool’s diameter as the radial DOC value.

Optimized Roughing Benefits

Optimized roughing improves metal removal rates (Q), reduces the amount of time spent in the roughing phase, and increases tool life, all while reducing the load on the machine, according to Ball.

“Instead of encasing the tool in 180 degrees of engagement, which creates a lot of heat and a lot of pressure, better metal removal rates are achieved with optimized roughing because machinists can take a 2xD DOC and use a 10 to 12 per cent stepover, depending on material. This means you generate less heat and have less radial engagement, which means you can accelerate feed rate and surface footage rate. This is what reduces cycle time,” he added.

This process uses multiflute (5-, 6-, 7, 8-, and 9-flute) end mills and a stepover technique.

The amount of stepover that can be used depends on tool diameter and the number of flutes on the tool. For example, a 6-flute, 0.5-in. end mill cutting 4140 steel can use a 10 to 12 per cent stepover. With a 7-flute tool, the stepover is only 8 per cent. Moving to a 9-flute tool reduces the stepover to roughly 3 per cent.

As the number of flutes increases, the stepover must decrease to maintain surface finish at faster feed rates. If the stepover is too large, feed rates must be lowered, and more heat is generated with the larger amount of metal removed in each pass. By decreasing the stepover, faster cutting speeds can be achieved. This requires more passes, but the metal removal rates are still higher than at slower speeds because of the increased feed rates.

Know the Tool

The number of flutes determines the stepover percentage because it determines the chip spacing. Tool diameter also plays a role. For example, a 0.5-in.-dia. tool with 9 flutes has less chip spacing than a 1-in.-dia. tool with 9 flutes.

Optimized roughing uses a large DOC and light radial engagement to maximize metal removal rates. Photo courtesy of Seco Tools.

“Niagara Cutter [a division of Seco] has a multiflute family of tools that is used for this type of cutting. They feature a 38-degree helix, large core diameters, and multiple flutes (6, 7, 9). The tools used for optimized roughing typically have some sort of corner protection (radius or chamfer) and are coated to provide both heat and abrasion resistance, typically an AlTiN coating,” said Bell.

Cycle Time Reduction

Overall cycle time is dependent on the part. If a part is near-net forged, for example, it will not require as much roughing as a solid block will. Another example is a mould cavity: It requires much more time to be spent in the finishing stage rather than the roughing stage because a smooth 3-D finish is required.

Optimized roughing is not for every part; it’s very component driven. If a part is a complex, 3-D component, optimized roughing is not going to be the most efficient way to get the highest metal removal rate during the roughing stage. When it can be employed, however, it can have a significant effect on cycle times.

“We have seen as little as a 30 per cent in cycle times and a high end of 80 per cent reduction,” said Ball. “In the upper range, the cycle time reduction also takes into account a reduction in rest roughing and semifinishing.”

According to Ball, the best use of optimized roughing is in situations that use the full flute length of the tool. Roughing long, straight walls is a good example of this.

Metal Removal Rate

When it comes to the overall manufacturing process, optimized roughing can typically remove 90 to 95 per cent of the rough stock on a workpiece. This leaves only about 1 to 2 per cent of the tool diameter as finish stock for removal.

“There might be some additional corner picking that you need to get closer to near net shape before you can move on to finishing, but this strategy takes the bulk of the material out,” said Ball.

Importance of Toolholding

High-precision toolholders are important in optimized roughing.

The holder needs to provide less than 0.0004 in. of runout. A precise holder ensures the accuracy of the process, whereas a less secure holder will cause undesirable levels of vibration at optimized roughing’s high feed rates.

“With any solid-carbide application in which you are trying to hold tight tolerances, the holders can make you or break you,” said Ball. “If you try to run these strategies and these processes in a collet that is not rigid or doesn’t contain the runout, you will struggle to achieve the metal removal rate and cycle time reduction this strategy can provide.”

Ball suggested milling chucks, shrink-fit holders, and high-precision collet chuck systems when using this milling strategy.

“You need good clamping pressure, good rigidity, and minimal runout,” he said.

Rigid workholding also is important to minimize vibration in the part or, in the worst-case scenario, movement of the workpiece.

Today’s advanced optimized roughing is only effective if implemented properly. And while similar in nature to other strategies, optimized roughing entails specific best practices that shops must adhere to and common missteps they must avoid to achieve optimum results.

Editor Joe Thompson can be reached at jthompson@canadianmetalworking.com.

Seco Tools, 248-528-5200, www.secotools.com

Optimized Roughing Tips

1. Use the right machine. Machines used for optimized roughing need two things: fast spindles and rigidity. The spindles must generate the necessary revolutions per minute for optimized roughing’s feed rates. The rigidity of the machine minimizes vibration and contributes to part quality.

2. Understand the power of CAM. It is impossible to program an optimized roughing strategy manually. You need to use a programming software package that will control the cutting strategy. But not just any programming software will work; it needs to be the right software for this application. A program designed only for high-speed side milling will not perform optimized roughing.

3. Don’t cut too deep. A cutting depth of 2xD that takes the full length of the cut in one pass is recommended. The shallow radial stepover enables the depth of the cut. A larger stepover would require a shallower depth of cut to achieve the same metal removal rates. However, a cut that is too deep, more than 3xD for example, creates cutting pressures greater than the tool can bear and causes deflection.

4. Use the tooling manufacturer’s recommended cutting parameters. Do not rely on the default cutting speed and feed rate data from programming software suppliers. Cutting tool suppliers develop the recommended cutting parameters after research and through years of experience. Tool makers optimize cutting data for the tool’s design and specifications and for the material group you are working with.

About the Author

Joe Thompson

416-1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

905-315-8226

Joe Thompson has been covering the Canadian manufacturing sector for more than two decades. He is responsible for the day-to-day editorial direction of the magazine, providing a uniquely Canadian look at the world of metal manufacturing.

An award-winning writer and graduate of the Sheridan College journalism program, he has published articles worldwide in a variety of industries, including manufacturing, pharmaceutical, medical, infrastructure, and entertainment.

Related Companies

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Industry Events

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI

17th annual Joint Open House

- May 8 - 9, 2024

- Oakville and Mississauga, ON Canada

MME Saskatoon

- May 28, 2024

- Saskatoon, SK Canada

CME's Health & Safety Symposium for Manufacturers

- May 29, 2024

- Mississauga, ON Canada