- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Looking Back: Milling Machines

"No other machine has received such an amount of abuse and been able to survive..."

- By Canadian Metalworking

- April 20, 2015

- Article

- Metalworking

As we continue celebrating the 110th anniversary of Canadian Metalworking magazine, in this issue we take a look at the state of metalworking technology 110 years ago with a focus on milling machines.

“The milling machine as it stands today is one of the most useful machine tools we find in the manufacturing establishment,” noted John Edgar in his July 1905 article, “Modern Milling Practice.”

In 1905, Edgar wrote that, “the milling machine has reached its majority. It has begun to demonstrate its usefulness. It, being an active factor in reducing the cost of production, has entered to a great extent in the progress that has been made in the machinery world within the last few years.”

As a matter of practicality for the 1905 audience, the article touched on best practices for operators at the time. “The milling machine, not unlike other machines in this respect, must be run with due regard to its efficiency and rated output…”

Necessary Conditions for Milling Machines:

- We must have a machine of size and style chosen in view of the work it is to do

- Our machine must be fitted with suitable fixtures for receiving work

- The cutters must be so proportioned so we may get the best results with the least expenditure of time in sharpening, and with the minimum amount of power.

Like today, shops at the turn of the 20th century were expecting their machines to finish parts with very little in surface finishing required: “If we go into a well-equipped manufacturing plant—such it must be to be in competition—we will see not only one or two, but dozens of the milling machines in groups fairly pealing off the metal, leaving a surface that requires little or no finishing touches.”

Types of Milling Machines:

In 1905 milling machines were made in four different styles, excluding specialty styles like the gear cutter, thread milling machine, rotary planer, etc. Here’s how the differences were defined back then, not too different from today:

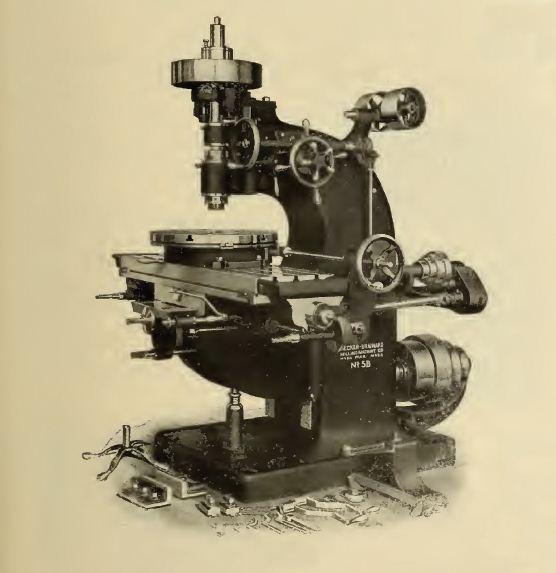

- The plain machine consists of a spindle set horizontally in an upright column. The column being fitted with a vertically adjustable knee, which carries the work table that has motion by power either parallel with or at right angles to the axis of the spindle, the latter motion being most used.

- The Universal machine, being similar to the plain machine, with the exception to that table, which is made to swivel in the horizontal plane, is fitted with a universal spiral and dividing head.

- The vertical machine is also identical to the plain machine, except that the spindle is set vertically and perpendicular to the plane of the table. This style is on occasion fitted with a rotary table which is used in milling circular work.

- The planer type is built on plans similar to the planer. Its general design varies with different builders and a much more notable degree than the other three styles.

Examples of Work Done:

- Figure 1: an example of surface milling on a vertical milling machine. Here will be seen the great advantage the vertical has over the horizontal machine for such work. The work is clamped in the table vise which makes it a good fixture for this piece.

- Figure 2 and 3: a miller has shown superiority over a planer in working out dovetails. Any machinist knows of the many accidents that are liable to occur while doing a job of this kind on a planer, such as breaking off of the point of the tool, gouging in of the tool or shifting its position, causing a change of the angle, in any case spoiling the work.

- Figure 4: this is an example of milling with the periphery of the cutter, and it is easily seen that the job can be done with the one cutter and with but one setting of the work.

- Figure 5: this is an example of where the same cutter is used to mill the inner and outer conical surface of the rings shown. This insures absolute accuracy of fit.

[gallery type="slideshow" link="none" size="large" ids="109914,109915,109916,109917,109918"]

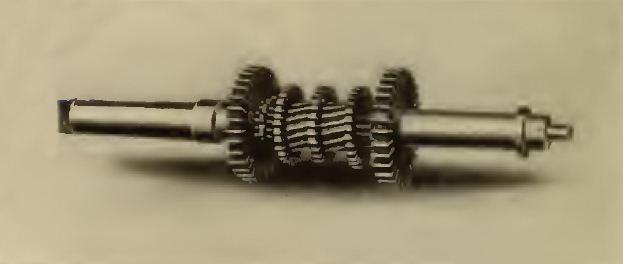

Cutters to be used:

In the vernacular of the metalworking industry in 1905, cutting tools were referred to simply as cutters. In this article Edgar includes some tips for selecting tools and why an operator needs sharp tools—suggestions that are as valuable today as 110 years ago:

"In selecting cutters it is best to have them as small as possible. It is also important to have the arbor of such a size to be able to resist the strains set up in milling.

Since the introduction of special high-speed steels, cutters have undergone many changes for the better.

For finishing work the carbon steel cutter has proven that they are best suited for this purpose, but when time spent in grinding and high speed are taken into account they have shown to be far inferior to the special steel cutters."

Effect of Dull Cutters:

Dull cutters are the cause of a good many failures in milling practice. Cutters must be kept sharp because (1) they require more power when dull, consequently the machine cannot work at its highest efficiency; (2) they strain both the machine and cutter arbor, causing the latter to spring, allowing the cutter to leave the work when any hard spots are encountered; (3) the surface left by a dull cutter is anything but satisfactory.

- Edgar finished off his treatment of milling practices by saying, “I am sorry that time and space available for such work does not permit me to be more explicit in some matters touched upon in this article, but hope that I may have the pleasure of treating more fully some of the most interesting features found in milling practice in the near future.”

Milling has featured prominently in many Canadian Metalworking issues since 1905. Check out our latest article on “Milling machines: faster, functional and compact,” which can be found on page 62 in the April 2015 digital edition.

About the Author

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Automating additive manufacturing

Sustainability Analyzer Tool helps users measure and reduce carbon footprint

CTMA launches another round of Career-Ready program

Sandvik Coromant hosts workforce development event empowering young women in manufacturing

GF Machining Solutions names managing director and head of market region North and Central Americas

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI