- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Casting by the Lake

Fiat Chrysler’s Etobicoke Casting Plant is a world leader in casting aluminum cross members

- By Nestor Gula

- July 6, 2016

- Article

- Metalworking

While much of the focus in today’s economy has been on banking and the service sector, Canadian manufacturing leads the world in some areas.

In the southwest corner of Toronto, Fiat Chrysler’s Etobicoke Casting Plant is a world leader in casting aluminum structural parts for Fiat Chrysler Automobiles’ vehicles.

“We are one of the best-kept secrets in Toronto,” said Plant Manager, Gerald Peterson. “Not many people know what we do, how we do it, and how good we are at what we do. [Casting] is an age-old process, and we have certainly refined it to a level that is extremely scientific now. There is no black magic involved.”

The plant sits on 27.4 acres of land a stone’s throw from Lake Ontario. The 280,000-sq.-ft. facility was built in 1942 as a casting plant for the war effort, making aircraft parts. Chrysler purchased the plant in 1964 and in 2010 invested $27.2 million to upgrade it to make structural parts. The plant employs more than 500 people working in three shifts, five to six days per week.

In rough numbers, the plant produces more than 4 million individual parts per year, according to Peterson.

“We pour 45 million lbs. of Silafont®-36 aluminum a year,” he said. “We pour 18 million lbs. of what we call 380 alloy, which is just a generic aluminum that is used in pretty much everything around the world.”

Silafont-36 is a low-iron alloy developed in Germany.

“This is a structural alloy; it will work and not break. The thing about Silafont is that it has a very low iron content. And that’s what gives it its elongation and elasticity characteristics. The iron content is extremely important,” he said. “We are the largest user of Silafont-36 in the world.”

The Silafont comes in ingot form from a mill in Wisconsin.

“We learned to recycle Silafont,” said Peterson. “The company initially said we could not recycle it, but we eventually figured out how to do it. We learned a lot about not just how to make parts out of Silafont but about the metal itself.”

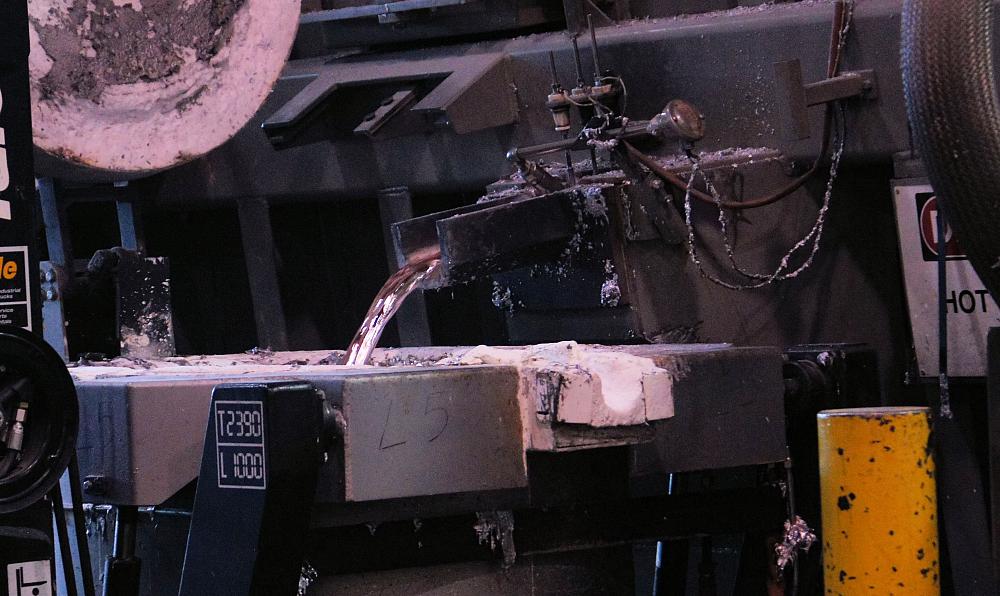

The other aluminum alloy is delivered molten in large vats.

“It comes in a truck with a big vat on it that has hot metal in it,” explained Ramsey Aljahmi, the manufacturing manager at the plant. “We unplug the vat and it goes into our furnace.”

The molten alloy is delivered from a mill located by the airport, which is a short drive away.

“They are just a few miles away, so it makes delivery pretty simple,” he added.

According to Aljahmi, using molten metal is a cost savings.

“We don’t have to expend so much energy to melt it. Their furnaces are more efficient. There is a cost saving because it is easier to make a large batch and bring it molten as opposed to making small ingots. Additionally, you can control your output a bit better. You can maintain the furnace better by using molten alloy.”

For those who might be familiar with the lost-wax method of casting using plaster or sand molds, the die casting that happens at the Etobicoke Casting Plant is a world away. It has 33 die casting machines ranging from 3,500 to 850 tons. The dies are made from H13 steel, a hot-work tool steel.

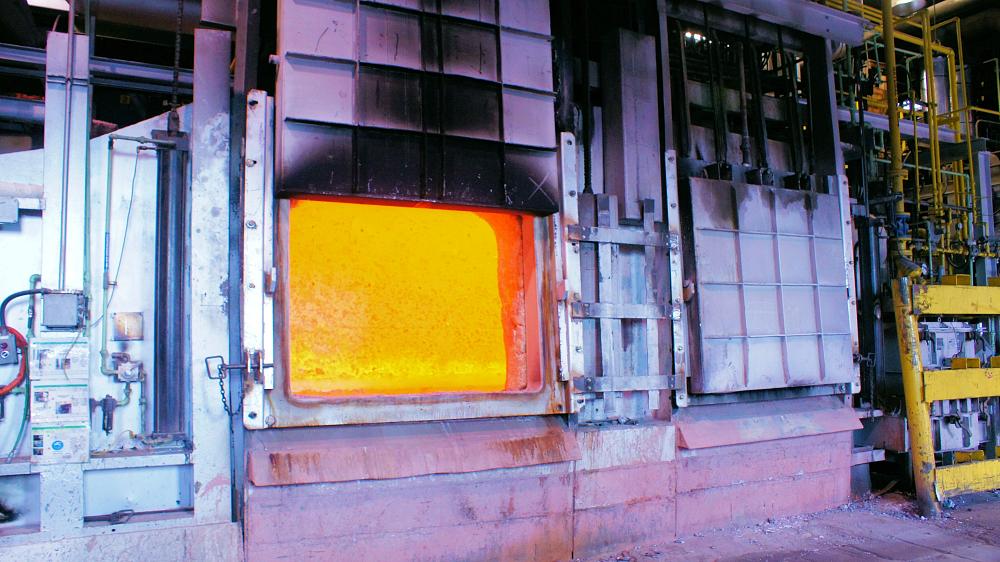

“We bring metal in. Then this molten metal is delivered under very high pressure to the die-cast machines,” said Peterson. “… for the cross member piece, we pour the molten metal into a sleeve, a piston rams the metal in, and the part is filled in 100 milliseconds. It is done, the process is over. There are water lines in the dies, and as the water circulates, it solidifies the molten aluminum to a solid and the die comes open a sprayer head comes down loosens the die and we start over.”

Once the part is removed from the die, it goes through a rigorous inspection regime. Each part is X-rayed to see if there are any flaws. Then each part is subjected to a fluorescent penetrant inspection. This involves spraying on a coloured penetrant, which seeps into the part.

When the overflow is rinsed off, the part goes through a black light booth where inspectors look at it. If they see the penetrant leaking out of an area, it indicates the part is cracked and it has to be thrown away.

“Every part goes through this process,” said Peterson. “It is an expensive process, but it is the only way to ensure that the parts will perform as they were designed. There are not a lot of people that can boast that they have the ability to do this.”

This inspection process is crucial because a large number of parts that the plant makes are complex cross members that are located on the underbody of the car and keep the frame together in the front.

“The process is complex. We are considered to be the most advanced structural die-cast plant in the world. We may be small, but we have a huge reach. We are considered a critical plant,” Peterson said. “We make structural parts, transfer cases, stators, adapters, and a lot of powertrain parts. We cast roughly 38 different parts for at least 15 different vehicles.”

In 2015 the plant made about 771,000 cross members out of Silafont and 3.5 million parts out of 380 alloy.

Inspecting cast parts after they are made ensures quality, but the dies themselves are inspected so the parts do not have defects in the first place. The dies live a hard life in the Etobicoke Casting Plant. The molten aluminum alloy is around 1,300 degrees F and is injected into them under very high pressure.

“And then you run water and cool the part and spray lube on it – there is a thermal contraction in the die [as it is] going from hot to cold,” said Peterson. “Over time it causes fissures and cracks and eventually it becomes so heat-checked that large pieces of steel start coming out.”

Finished cross members will eventually be located on the underbody of the car to keep the frame together at the front of an automobile.

The life of a die depends on its shape and the number of shots it has taken, meaning the number of times it has been used.

“We are always trying to extend the life of the dies because they are very expensive,” he said. “We repair them in-house but we do not have the tools to make them; they are subcontracted out.”

Peterson and his team gladly talk about the casting work they do, but the conversation turns serious when they talk about safety in their plant.

“The most important thing we do in this plant is safety. You come in in the morning, you go home the same way. Safety – it is the most important thing that we do,” he reiterated. “People have to have an environment where they are safe. We just received a prestigious award from the North America Die Casting Association where we were recognized to be an outstanding safe plant in our industry. We are considered to be one of the safest die-cast plants in the world, and we are pretty proud of that.”

The plant holds frequent timed fire drills and records the results and examines how to do better. It has a tornado shelter as well.

Rod McGill, the president of the plant’s union, Unifor Local 1459, has been in the plant for 32 years and has seen its evolution firsthand.

“I’ve seen a few changes. When I started here, you could not see that wall,” he said, pointing to a wall about 10 ft. away. “There was smoke and dust and fumes. Everybody had to wear crash helmets and leather aprons. There was metal exploding out the dies. There were obstructions where you could trip. There were a lot of safety issues. People could not get out of here fast enough. We’ve come a long way.”

He attributes the plant’s success to the good relations the union has with management.

“Me and Gerry [Peterson] are both toolmakers. This plant is family. People on the floor have a third generation of family here. There are some people who live literally across the street from here,” he said. “The objectives are the same: keep the plant open and get more work. That common cause encourages us to work together.”

Both Peterson and McGill agree that there are issues that they won’t agree on, but their common goal of the plant’s success unites them.

“We don’t just disagree to disagree because then we won’t get anywhere,” said McGill. “The relationship between union and management is very good, and that is even recognized nationally. That is really good news for us that we have that, especially coming from a plant that was nearly dead.”

The future of this nearly dead plant is robust, according to Peterson.

“We realize we are in a supercompetitive business and every day we have to improve. It is nothing but continuously improving,” he said. “You have to get better if you want to survive. We collect more data than any die-cast plant in the world. By having all this data, we know and understand how to improve. The business model that Sergio Marchionne brought to us when Fiat took over is absolutely the best in the world bar none.”

Changing car technology means that the inclusion of cast aluminum alloy parts will be more prominent.

Peterson said, “They’ve done about all they can do with engine and transmissions at this point with the technology we are using. The next step, the only way to get better fuel economy, is to make lightweight vehicles. And I think the numbers speak for themselves. Since 1975 you can see the upward trend. Right now we are sitting at 394 lbs. of aluminum per vehicle. Not only are we making more vehicles, but we are also putting more aluminum in them. That is the only way the car is going to get lighter, unless you want to use some carbon-based materials, which no one can afford to buy.

“So here is the challenge: From 2015 to 2025 we are going to go to 550 lbs. of aluminum per vehicle. We understand this trend. There are likely capacity issues in the world that will not be able to support this trend, but we are well-positioned for it because a lot of these structural components will be aluminum. We understand Silafont and structural parts. I believe the Etobicoke Casting Plant is positioned well for the future.”

Contributing writer Nestor Gula can be reached at nestor.gula@yahoo.ca.

All photos courtesy of Nestor Gula.

Fiat Chrysler Etobicoke Casting Plant, 416-253-2300, www.fcanorthamerica.com

About the Author

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Automating additive manufacturing

Identifying the hallmarks of a modern CNC

CTMA launches another round of Career-Ready program

Collet chuck provides accuracy in small diameter cutting

Sandvik Coromant hosts workforce development event empowering young women in manufacturing

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI